Mirovα, Creating Sustainable Value - April 2025

March: awaiting sentence

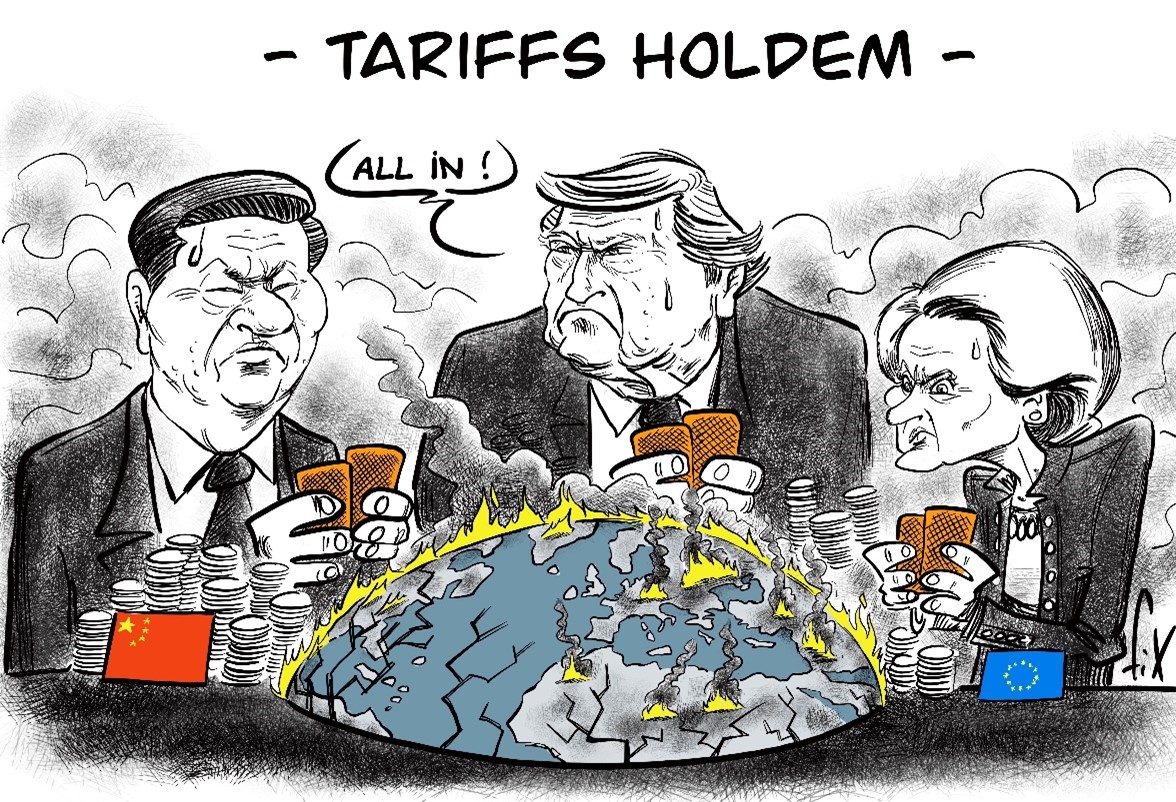

Whether they have already been introduced or are in the pipeline, it was the increases in customs tariffs that set the tone for the markets in March. Certain raw materials, such as steel and aluminium, and certain countries, such as Canada and Mexico, had already been the subject of targeted announcements, while the rest of the world was anxiously awaiting Donald Trump's Liberation Day on 2 April. The stress generated by this pricing policy has pushed all world markets into the red, particularly in the United States, down by around 6%, and in Europe, down by around 4%1. These concerns were compounded by profit-taking, encouraged by the meagre progress on the potential ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine.

Against this backdrop, European assets nevertheless held up better than US assets. This can be explained by the announcements of the German government, which is taking the path of recovery with an investment plan of €500 billion in infrastructure and €400 billion in defence over 10 years1. Europe is also benefiting from a slight improvement in economic publications and surveys, notably the PMI indices2 in France and Germany and the INSEE and IFO surveys. Another piece of good news is that inflation is still decelerating, coming in at 2.2% for headline inflation and 2.4% for core inflation3, compared with 2.3% and 2.6% the previous month. The ECB cut its key rate by a further 25 basis points to 2.5%1.

In the United States, confidence continues to erode, and this is beginning to show. While employment is still holding up, with over 220,000 jobs created over the month, businesses and households are worried about a return of inflationary pressures, as much higher import costs will have a negative impact on margins and purchasing power. The 5 to 10-year inflation expectations revealed by the University of Michigan index jumped to 4% in March, reaching levels not seen since February 19931. For the time being, the Fed4 does not appear to be changing its interest rate policy, and is assessing the impact of the current trade tensions on the economy. Even so, it has reduced its quantitative tightening, thus becoming slightly more accommodating.

This context had a bearish impact on the credit market, marked by a widening of spreads5 : a spread of just under 10 basis points on Investment Grade6 and 50 bp on European High Yield7. In the United States, the 10-year yield remained stable at 4.2%, while the German Bund yield rose by 30 basis points to 2.75%1. A rise achieved in just over a day, an exceptional event. European long yields8 also rose in the wake of the Bund. Short rates remained stable. We are therefore seeing an acceleration in the steepening of the curves, with a spread of 70 basis points between 10- and 2-year rates at the end of March1.

Although the Chinese stock market was not spared by international uncertainty, the country nonetheless benefited from good macroeconomic data. Industrial production grew by 6% and retail sales by 4% year-on-year in March, showing a slight acceleration since the start of the year. At its National Congress, the Party reiterated its GDP growth target9 of 5% for 20251.

Global uncertainties continued to benefit gold, which gained 10% over the month and 18% between the start of the year and the end of March. The dollar depreciated sharply against the euro. The latter gained 4.5% over the month, a massive movement, with a record session of 1.7% increase against the dollar over the day. There was no fall in oil prices in March, only in gas prices1.

Chart of the month

Source: Budget Lab at Yale.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of futur performance.

Macro review and outlook

The turning point

The 2nd of April marked a turning point, with Donald Trump announcing that he would be imposing much higher tariffs on products entering the United States than had previously been anticipated. He has plunged the world and the stock markets into the unknown. Whether this is a negotiating tactic or a dogmatic approach, it is still difficult to see clearly, but the negative repercussions on financial assets and the economy would appear to be very real.

Act 1: Reciprocity hard to swallow

The verdict came down on 2 April and it was harsh. While Donald Trump has spared the American continent overall, he has hit other regions of the world hard.

- Asian exporters were among the hardest hit: Vietnam, Thailand, China... China has been hit with 34% additional taxes on top of the 20% already in force; Japan with 24%10.

- The European Union got a 20% surcharge10.

With a two-part "reciprocal pricing plan".

1) From 5 April, all US imports are taxed at a non-negotiable rate of 10%10.

2) From 9 April, trading partners are subject to a differentiated additional tax, with the exception of Canada and Mexico, which are affected by earlier announcements.

The US government has threatened further increases for any country that takes what it considers to be retaliatory measures. China has chosen to follow this path, announcing very quickly in return that it is increasing its own tariffs on products from the United States. While the European Union, through Ursula von der Leyen, believes that negotiations are still possible.

Act 2: Partial (?) capitulation by Trump under pressure from bond markets

On 9 April, Trump announced that he was suspending reciprocal tariffs for 90 days for countries that had not retaliated, maintaining the minimum tariff of 10%, except for China, on which he imposed a rate of 125%11.

From Liberation Day to Recession Year?

While Trump explains that the effects of his customs policy will be positive for the US economy, economists are more circumspect, if not downright worried. The United States will be the country hardest hit in terms of growth and inflation among the major developed countries.

Tariffs will in fact mean a surcharge on American consumers and will erode corporate margins. This represents a "fiscal shock" for the US private sector of around 2.5% of GDP. This will raise inflation by a further 1 to 2 percentage points and could cost the country more than 1 point in growth. Moreover, economists currently estimate the probability of a recession in the United States at over 40% within the next year, compared to 10% at the beginning of the year11.

Additionally, this pricing policy is creating a lasting supply shock by disrupting value chains and worsening financial conditions, as evidenced by the rise in long-term rates and credit spreads, and the fall in equity markets and the dollar.

While the 90-day pause in US tariffs may have allayed short-term fears of a trade and financial shock, the tariff structure remains complex and uncertain (25% on steel, aluminium, and cars, 140% on Chinese products, etc.)11. This will continue to weigh on business investment decisions and consumer confidence.

How then will the Fed respond?

The market is anticipating 4 rate cuts over the year, including one in June, with a high probability11. However, this is not what the institution is currently saying. Changes in its policy will depend on developments in the labour market, which has not yet been confronted with the consequences of the rate hikes, and on US inflation, which is expected to rise this summer.

On the long end of the curve, a number of structural factors, including above-target inflation, concerns about the Fed's independence, a term premium and a higher risk premium, argue in favour of structurally higher rates.

Bad timing for the eurozone

The outlook for growth remains uncertain at this stage, with two opposing forces at play: the positive impact of investment plans on the one hand, and the uncertainty linked to developments in US policy on the other.

Even if the recessionary effect of the increase in customs tariffs appears to be less marked in Europe than in the United States, with exports to the US accounting for just 3.5% of the eurozone's GDP, certain sectors (automotive, transport, aviation, pharmaceuticals, wines and spirits, etc.) and certain countries, notably Germany, the EU's leading exporter, will be particularly hard hit11. Similarly, the rise in economic uncertainty and the deterioration in financial conditions, which will delay business decision-making and penalise investment and employment, as well as increased competition from China (the European market being the main substitute for the US market), are likely to continue for several months yet, weighing on activity.

This is why we are revising the zone's GDP growth downwards in 2025, to +0.7% (vs. 1%) and 1.5% in 202612.

These tariff announcements come at a time when the European Union can look forward to some good news: improving PMI indices, with a recovery in new orders, particularly in Germany; a downward trend in interest rates favourable to credit; and disinflation well established, with core inflation13 in services at 3.4% compared with 3.7% the previous month. But above all, Europe should benefit from Germany's vast investment plan. According to a central scenario, and assuming a multiplier of 0.3 for defence spending and 1.2 for infrastructure spending, Germany's GDP growth surplus could be around 0.3 point from 2025, then 1 point in 2026, rising to over 1.5 points in 2027 and 202814.

So, this tariff war should reinforce the disinflation movement, even if the EU retaliates against certain US goods. The slowdown in foreign demand, global overcapacity, falling energy and commodity prices, and the euro's appreciation against the dollar all point to lower inflation. This should give the ECB sufficient visibility to continue its monetary easing, with a target rate that we now estimate at 1.75%12.

What China has in common with Europe is that it can count on stimulus packages to ease the tariff war with the United States. As a result, the authorities took some strong policy decisions aimed at supporting domestic demand and growth at the most recent sessions of the party's national congress at the end of March, even if their target of 5% growth by 2025 seems quite ambitious as things stand. The consensus was for 4.5% before the price escalation of the last few days14.

The plan is to boost domestic growth through urban redevelopment projects, an extension of the consumer goods recovery programme, an increase in minimum wages, an extension of social security cover, childcare subsidies, etc.

At the same time, the authorities are focusing on technological development, with a wide range of measures to support continued innovation and adoption of technologies, including broader support for capital markets and financing.

There is one unknown factor: how far will the tariff war go, and to what extent will it break the momentum of confidence that China seemed to have gradually regained at the start of the year?

On US time - An expert's view

In a complicated market environment, the link between sustainability and financial performance can become even clearer.

Jens Peers, Chief Investment Officer of Mirova in the United States and portfolio manager, believes that higher effective tariffs rates are likely to lead to higher inflation, particularly in the US, which could result in a consumer-led recession. Additionally, globalization as we have seen it in the past few decades will be redefined. The uncertainty around future developments will lead to volatility and very likely pressure the markets, as demonstrated by the very sharp fall in world stock markets following the announcements on 2 April: almost -10% in two days. Despite the recent weakness in the markets, there is still room for further downside from here, but we are likely to see both good days and bad days in the equity markets. If we do see more favorable agreements between the U.S. and other countries, this would be a positive for equity markets, but we continue to assume an overall higher effective tariff rate and continue to see the potential for recession.

"In this period, many sustainable investment themes could perform well compared to other sectors or themes, as they are generally more resilient and higher quality", according to Jens Peers. This is a phenomenon we have already seen in the markets in the wake of U.S. President Trump's announcements, with many companies in the renewables, utilities, and pharmaceuticals sectors holding up better than the broad market.

The disruption to international trade can be compared to a sustainability risk that is materialising. Companies that have worked on the resilience of their supply chain and short circuits are at an advantage. Additionally, all else equal, a slowdown in world trade and shorter supply chains would be a positive for the environment due to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. This will also push companies to focus on their resilience.

So while the Trump administration’s actions could inadvertently benefit the environment, we may not be able to say the same for social issues even if the intent is to bring jobs back to the U.S. "We can expect price increases that are likely to affect the poorest people most, not only in the United States, but throughout the world."

What next? There's still one big unknown: geopolitics. While the world is focused on tariffs and markets, it is overlooking Russia, Israel or Iran, which could be at the center of President Trump's future decisions.

The Long View

Can China escape the Japanese scenario?

Comparisons between what has happened to China since the Covid crisis and what Japan went through 35 years ago are rife, and for good reason. Three decades apart, the two countries share some striking similarities: demographic decline after decades of sustained growth in their respective populations and economies, a property crisis, doubts about the quality of the debt carried by the banking or proto-banking system, massive exports which are declining after years of maintaining accepted mercantilist policies based on a patient move upmarket through gradually increasing value-added content. The parallel therefore seems obvious, and so does the conclusion: China will go through in the 2020s and 2030s what Japan endured throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

It looks like a done deal. Deflation, bank consolidation, ballooning public debt, sluggish corporate margins and the erosion of technological dominance are all on the agenda... at least in theory. And only in theory, because it seems to us that the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party have anticipated this scenario and are equipping themselves with the means to avoid it, especially as these similar trends are not taking place over the same time scale. So, what are the chances of China avoiding following the Japanese counter-model?

The Challenge of Demographic Recovery

We have mentioned the salient feature of the rest of the 21st century on several occasions: the demographic slowdown, if not generalised, then at least on the way to becoming so, in proportions sufficiently marked to lead to a decline in the next century. Everyone is familiar with the case of South Korea, of course, where the fertility rate is plummeting to barely 0.8 children per woman of childbearing age, but also Singapore (1 child per woman by 2022), Spain (1.2), Italy (1.2), Poland (1.3), Thailand (1.3) and Uruguay (1.5)... all continents are affected, with the exception of Africa, although the Maghreb and the Horn of Africa seem to have slowed down over long trends (leaving aside troubled periods, such as the terrible civil war in Algeria at the end of the 1990s, which disrupts the reading of trajectories).

Several countries are working hard to curb the phenomenon. Hungary (1.5) is working towards this with very generous policies for couples who have children. Russia (1.4) is also trying, but the results are not living up to the hopes placed in these policies to boost the birth rate. There's no point in prolonging the suspense: China won't have any more success than other nations that have tried the experiment. Xi Ji Ping has put in the effort, but the fertility rate remains hopelessly below the 2.1 children per woman needed for generational replacement, at 1.2 children per woman, falling steadily since it hit 1.8 in 201715.

The reasons are not very different from those in the West: property costs, urban overcrowding, school fees and people's desire for greater freedom and material comfort. The difficulty of forming relationships that can withstand the test of time is also one of the reasons recently put forward; this is undoubtedly a by-product of the rate of urbanisation, since sociologists have known for a long time that the chances of meeting someone are higher in the city, and young people are perfectly aware of this, which paradoxically makes them more inclined not to make a choice, since there are so many alternatives. A change of mentality, or of lifestyle, cannot be decreed: if Mao Tse Dong had difficulty in forcing Chinese couples, particularly in the more rural western parts of the country, to limit themselves to one child, how can we imagine that his successors will succeed in convincing them to have more than two when they have now largely had to cluster in vast urban centres?

Demographic trends are one of the pillars of economic activity: with constant productivity and access to resources, population change will appear positively correlated with economic growth. How can China avoid facing the consequences?

Production-led recovery: underestimated potential for further growth?

Mao's policies had the effect of shifting China's demographic and macroeconomic cycles, which Deng Xiao Ping then unlocked. 30 years on, this time lag is still having an impact. In short, China's demographic peak has not coincided with its productive peak16.

While Japan, to continue the comparison, was able to demonstrate overwhelming superiority in consumer electronics at the end of the 1980s, for example, which only diminished afterwards, paradoxically the Chinese still have considerable room for catch-up in many sectors. In civil aviation, for example, with Comac's C919; in military equipment, with the latest J-36, a sixth-generation fighter jet from Chengdu Aircraft Corporation; in electric and non-electric vehicles from BYD, SAIC and XPeng; in rail mobility, with world leader CRRC; in tyres, with Zhongce Rubber Group Co, drones with DJI, Artificial Intelligence with SenseTime, ByteDance or Baidu, industrial robots, asset management, insurance, agricultural machinery, mining equipment, electronic chips, robotics... We could multiply the examples ad infinitum to illustrate that there is undoubtedly still an enormous amount of market share for Chinese companies to take throughout Asia and even the world, if the latent conflict with the United States is resolved in a reasonable way16.

Their technological lead in several areas, such as lithium-ion batteries, and the progress they are still making, appears to be greater than that held by their Japanese neighbours at the end of the 1980s, even though they have not yet really ousted their competitors - quite the contrary. If there are no major obstacles to the free movement of goods in the future, then China's potential seems far from exhausted. And the alignment of industrial and technological agendas with that of the Chinese authorities, who are aiming for total autonomy in certain sectors, notably semi-conductors, adds to the likelihood that a large proportion of these developments will go ahead.

Last seal to be opened: real estate. Here again, the authorities seem to have tackled the problem well.

One last brake: real estate or growth for dummies

Will this unsaturated potential for industrial recovery be enough to offset the negative effects of the real estate slump? We think so. As a reminder, the property development and construction sectors offer massive, rapid and almost mechanical gains in GDP. That's something any political leader on any side of the political spectrum would love to hear, especially since, all other things being equal, recent infrastructure helps to boost the productivity of all the economic agents who use it. On the other hand, infrastructure decline quickly penalises growth per se, not to mention the fact that the fall in house prices, even though the housing stock is no longer growing, impacts the wealth effect and, ultimately, household consumption.

The development system in China after the departure of Deng Xiao Ping was largely based on this property boom, fuelled by the massive rural exodus of populations growing at a high rate and becoming richer, with the creation of a vast middle class of at least 300 million people. The virtuous circle thus generated has magical effects... until it jams and corrupts, drifting into a vicious circle where deaths free up housing that the next generation does not need in the same proportions, creating falling prices, unpaid bills, and bad debts on bank balance sheets. Rather than resorting to mass immigration to prop up prices, or offering public stimuli for house purchases, which might have made sense, its authorities opted to smooth the fall, let some players collapse and purge the segment by cushioning the shock to avoid worsening the wealth effect.

Conclusion: China in 2025 is not Japan of the 1990s

China is facing threats more or less similar to those faced by Japan in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, its authorities and industrialists have taken steps to ensure that it does not suffer the same terrible fate of prolonged economic stagnation, thanks to choices that seem sensible to us, and also “thanks” to the imbalances introduced by Mao and corrected by Deng Xia Ping.

The great economic leap forward that China has made since the latter's term in office should therefore not end in a slump: the emergence of industrial capacity, technological breakthroughs and networks of access to natural resources ensure that the headwinds of demographic decline and the resulting pressure on the wealth effect, via property, should make it possible to embark on a period of growth that is admittedly less dynamic, but still satisfactory. Any air gaps could easily be corrected by occasional Keynesian stimulus packages.

A rosy future therefore seems to be in the offing... unless the United States, aware that it is competing in the core areas it intends to dominate - AI, robotics, defence - decides to close the West to China. This is also what is at stake on the Ukrainian front: the delimitation of China's sphere of influence.

Summary of Market views

The information given reflects Mirova's opinion and the situation at the date of this document and is subject to change without notice. All securities mentioned in this document are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute investment advice, a recommendation or a solicitation to buy or sell.

1Source: Bloomberg, as of April 2025

2PMI (Purchasing Manager's Index): indicator of the economic state of a sector

3 Core inflation: inflation that excludes certain volatile elements, generally food and energy prices

4Federal Reserve (Fed): United States Central Bank

5Spread: difference between Corporate yield and risk-free rate

6Investment Grade: Agency ratings between AAA and BBB- on the Standard & Poor's scale, corresponding to a low level of risk

7High Yield: Agency ratings below BB+ (BB+ included) on the Standard & Poor's scale, corresponding to a high level of risk

8OAT: Obligations assimilables du Trésor (French government bonds)

9GDP (Gross Domestic Product): Total value of goods and services produced in a country over a given period, usually a year

10Source: Bloomberg, as of April 2025

11Source: Bloomberg, as of April 2025

12Source: Mirova, as of April 2025

13 Core inflation: Inflation that excludes certain volatile elements, generally food and energy prices

14Source: Bloomberg, as of April 2025

15Source: data.worldbank.org, as of 2022

16Source: Mirova, as of April 2025

17Invest in both extremes, high-risk and low-risk investments, while excluding medium-risk investments

News

Discover the 2024 Impact Report for Mirova Global Green Bond Fund.

Trump is making a comeback: are Europe and China next?