Mirovα, Creating Sustainable Value - July 2024

Bi-annual market review & outlook

IT’S POLITICS STUPID! 1

Following European Parliamentary elections that saw significant gains for the far right in multiple countries, France experienced three weeks of political mayhem fuelling uncertainty in the markets due to hasty preparations for snap legislative elections. Now that France’s far-right parties have failed to secure an absolute majority—or even the relative dominance they expected—the French OATs1-Bund spread is back to acceptable levels for financial authorities, while the stocks of French banking and insurance groups have rallied. But for how long? In the near term, risks abound, with an institutional situation made precarious by a national assembly (legislative body) now clustered around three blocs of similar size, jockeying for position. More broadly, the situation in France just replicates electoral trends emerging in western countries over the past decade: Greek debt crisis, Brexit, the first Trump administration, the alliance between Italy’s La Lega per Salvini Premier (LSP) and the Movimento 5 Stelle (L5S), and so on.

What underlying reasons explain this polarisation of results at the ballot box? For a growing majority of citizens, globalisation is no longer a boon. Loss of control over borders, industrial offshoring, rising inequality and poverty or fears arising from an economic model that exhausts planetary resources—similar causes produce similar votes. A common theme of public outcry all over is the impression that some ways of life are being destroyed for the sole benefit of a few urban centres inhabited by elites that hold the reins both politically and economically.

It’s high time elites heard this cry, not as an opportunity to explain to the people that they are mistaken and that business as usual can continue ad nauseam,2 but to get down to work for them and organise the partial de-globalisation underway in an orderly fashion, which in our view cannot but involve industrial relocalisation, environmental awareness, and an end to the winner-take-all system. If elites continue to turn a deaf ear, however, we have no doubt that opening night will follow hard on the heels of the dress rehearsal we just witnessed. Voter secession, then debt crisis, followed by financial and economic crises will be the three acts of a drama whose plot has all the subtlety of a charging rhinoceros.

For now, the summer break and Olympic games are upon us. After a dizzying first half of the year, markets too are looking forward to a pause before diving back into the possible consequences of the US elections.

The first half in 10 key facts

Macroeconomics: controlled normalisation

UNITED STATES: SOFT LANDING, 1 - NO LANDING, 0

No landing, soft landing? At the start of the year, all options were on the table. US indicators showed no sign of slowing through March, when the brakes began to kick in.

At Mirova, our central scenario was based on a soft landing, which was optimistic at the time. It has, however, been confirmed over the months, supported by a number of indicators. Activity in the United States remains quite healthy, though macro surprises have pulled back into negative territory recently. Industrial and manufacturing output, hitherto buoyed by stimulus plans and repatriation of some production activities, seems to be slowing. The property market has not faltered: prices are still high, though new developments and transactions are weakening. The labour market, still very solid, is gradually returning to pre-covid levels, while wage inflation is progressively slowing. Investment is holding up thanks to high business margins. Consumers, however, especially those on low to moderate incomes, are beginning to show signs of weakness, if the latest retail sales figures are anything to go by, or the rise in default rates on credit cards and car loans (bearing in mind that they are rebounding from a low point). Overall, US growth ended the half-year in line with potential, i.e. GDP3 growth close to an annualised rate of 2%,4 and consistent, at least for now, with a successful soft-landing scenario.

POSTPONEMENT OF RATE CUTS AND A FIRST TASTE OF EASING

The markets began the year expecting seven rate cuts from the Federal Reserve in 2024, based on a rather recessionary economic scenario, to which we did not subscribe in the least, and a highly disinflationary one, to which we did. None of these cuts has so far taken place on the US side, as disinflation floundered in the first few months of the year while the US economy held up. The Fed consequently turned to a ‘higher for longer’ policy, which the market has come to accept. However, investors do not anticipate any further rate hikes. The dynamic is more about postponing rate cuts until the end of the year and into 2025/2026, than cancelling them outright.

While the path has been a thorny one, the ECB5 has finally succeeded in distancing itself from the Fed,6 announcing its first rate cut in June. Here again, the pace appears slower than anticipated at the start of the year, when the market expected six rate cuts. The ECB is disinclined to cut too quickly, given the improvement in macro dynamics and the rigidity of service prices. In particular, the ECB will be watching wage inflation, which we expect will continue to normalise.

For its part, the Japanese central bank raised rates by 10 bp7 in March for the first time since 2007, to a range of 0%10 to 0.1%7 (vs -0.1%7 previously) and has pledged to reduce its balance sheet this summer. We expect monetary tightening to continue, but its pace will depend on the strength of real wages and household consumption. Furthermore, the weakness of the Japanese yen, which is at an all-time low against the dollar, increases the risk of stagflation over the next few years and poses a challenge for the BOJ.8 In March, the Swiss National Bank lowered its key rate by a surprising 1.75%.7 to 1.5%7 before making a second cut of 25 bps7 in June. In May, the Swedish Riksbank also cut its main key rate for the first time in eight years, to 3.75%.7 The Bank of Canada followed suit, cutting rates in June. The downward trend now dominates in the policies of central banks around the world.

A PERSISTENT DICHOTOMY BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN EUROPE

Southern Europe has been the main beneficiary of the European Union’s stimulus plans and of the recovery in services. Expectations of rate cuts by the ECB are also in its favour. Italy, in particular, is set to become one of the primary recipients of European aid over the next two years and is reaping the rewards of its healthy industrial sector, while Spain is benefiting fully from the strength of its tourism sector and could deliver GDP growth of over 2.5%7 in 2024. However, while the countries of southern Europe exhibit clear momentum, growth remains sluggish in Germany and France.

UNPRECEDENTED GEOPOLITICAL RISKS: IMPOSSIBLE TO ASSESS AND THEREFORE DISCOUNTED

The world has entered an unprecedented period of aggregate geopolitical risks, risks that the market cannot assess and which it has no choice but to ignore. At this stage, the situation has had no impact on risky assets, despite the proliferation of acute crises between nuclear, oil and industrial powers pushing the limits of indirect confrontation ever further.

EXCELLENT BUSINESS RESULTS

Corporate earnings reached record levels, particularly in the US technology sector. As well as an increase in sales, there has been an expansion of margins. Rising productivity in recent quarters, particularly in the US, has moderated unit labour costs, helping to drive the healthy trend in margins. The market is now expecting 11%9 EPS10 growth in the United States and 4%12 to 5%12 in Europe for the year, which we consider reasonable. On a global scale, this means +8%12 EPS growth in 2024 after the stagnation of 2023, reflecting an overall positive global macro dynamic since the start of the year. As a result, there has been a greater expansion of multiples in the United States than in Europe, contributing to the outperformance of US equities. The rise of the S&P 50011 since the start of the year has been generated half by earnings growth, and half by P/E12 increases.

Markets: equities rule the board

OUTPERFORMANCE OF STOCKS

Whether in the United States or Europe, rising interest rates did not penalise risky assets. Risk appetite remained strong and, combined with good corporate earnings, considerably boosted equities.

In Europe, the banking sector performed very well, particularly Italian and French banks, at least until the dissolution of the French National Assembly. We have been overexposed to this sector since the end of 2023, as it remains underweighted despite improvements in earnings and multiples. We are neutral at the start of the second half of the year, given that the financial sector is on the front lines of rising political risk in Europe.

In terms of style, momentum-driven management significantly outperformed, thanks to technology and, more generally, mega-cap growth companies with high margins, strong growth and low debt, which are more immune to this high-interest-rate environment. Quality/defensive themes bounced back at the end of the half-year against a backdrop of rising risk aversion, but failed to make up the lost ground accumulated since the start of the year. Within the value segment, only banks really performed, and the start of the year was complicated for small caps. Overall, cyclical stocks outperformed defensive ones, but some segments are starting to look less attractive in terms of valuation given the macro dynamics, leading us to adopt a more neutral stance at the start of the second half of the year.

The high weighting of US large caps has held down both realised and implied volatility on the equity indices. However, the end of the half-year began to see some profit-taking in this segment, even though the fundamentals remain very solid at this stage, with higher growth than the rest of the market expected, and a positive trend in recommendations, among other things.

HYPERFOCUS OF PERFORMANCE AND GROWTH ON US TECHNOLOGY

Since the start of the year, just five stocks—Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet and Meta—together account for 60% of the S&P 500’s performance.13 This clique turned in performances around 45%,16 and accounts for some 1/416 of the index by market capitalisation. More broadly, earnings growth in the US tech sector (S&P 500 Info tech index) was 27%.16 (i.e. 3x the average growth of the S&P 500), with sales growth of 8%16 (double the average for the S&P 500), while margins are rising steadily and now comfortably exceed 25%,16 double those seen in the S&P 500 excluding Tech.

This dazzling growth in profits continues to be underpinned by a number of structural factors: the development of AI,14 the Biden administration’s legislation (CHIPS and IRA), the development of the Internet of Things (IoT), the ‘metaverse’, cybersecurity and, of course, continuing digitalisation of the global economy and the tech-intensive energy transition.

Implied growth in the US market is therefore linked to technology companies, which have the strongest expansion of P/E multiples: more than 28x expected earnings over 12 months, or 7 points more than a year ago. In 2001, when the internet bubble burst, we were at 47. If we exclude the 10 largest capitalisations in the S&P 500, the average P/E ratio falls to 18. Tech’s premium over the S&P 500 is now 35%,13 the highest it’s been since the mid-2000s.

This hyperfocus can also be explained by the massive flows from US retail investors and the growing weight of ETFs15 in the market. Through indices, investors position themselves mainly on large caps, and the indices themselves contribute to concentration by boosting the capitalisation of certain stocks. This type of investment also helps to reduce volatility, which in turn attracts more investors.

AN APPETITE FOR CREDIT

Credit, especially high-yield credit, performed well. The market appears to have adopted our conviction that it was better to favour exposure to quality companies with access to capital markets rather than governments. CoCo (Contingent Convertibles) also performed very well, before going through a more difficult period at the end of the semester—like the rest of the asset class—following the dissolution of the French National Assembly.

The dichotomy in economic performance between France and Germany on the one hand, and Southern Europe on the other, has resulted in an outperformance by peripheral European countries. The result has been significant tightening of spreads in Italy, Spain and Greece.

On the primary market, there was an imbalance between supply and demand, with a scarcity of high yield, despite good issuance volumes in the middle of the quarter. Many securities were upgraded to investment grade16 thanks to the strength of balance sheets. In the eurozone, the implied default rates on investment grade and high yield seem consistent with a moderate growth scenario we are comfortable with. The rise in default rates is currently more of an issue for unlisted companies, such as VSEs17 and VSIs.18

GOLD SOARS TO NEW HEIGHTS

Gold’s performance has disconnected from that of real interest rates, due in particular to the voracious appetite of several central banks—with China in the lead, followed by other emerging countries—as well as renewed interest on the part of Asian households. Gold also remains popular against the dollar in a general context of de-globalisation; this trend furthermore reflects aversion to geopolitical risks. The glittering metal has reached new all-time highs, even as equities continue to rise. Such safe-haven and risky assets advancing in tandem is rare, but the interest rate situation, after two years of increases, is creating circumstances different from those of the last thirty years. Over the first six months of the year, gold gained 9% in dollar terms,19 as much as the S&P 500 and more than global equities outside the United States.

This rise can also be explained by the underperformance of sovereigns and demonstrates a certain mistrust of fiat currencies, something the volatile success of bitcoin also illustrates in its own way.

THE DOLLAR STAYS STRONG

The dollar stands out for its strength. It has appreciated in line with the Fed’s higher-for-longer policy. Rising geopolitical uncertainties triggered the safe-haven aspect of the greenback, and US assets benefited from an influx of international savers, with the rising dollar and rising assets feeding off each other.

CONSUMERS AT THE OLYMPICS

Outlook for H2 2024

We started the year with a more optimistic view than the consensus on growth prospects for the US, European and Chinese economies, and the semester has ended with better than expected macroeconomic data. Given the performance of the last six months, the United States should, barring exogenous shocks, achieve annual growth of close to 2.5%,20 while China should exceed 5%20 and the Eurozone should grow by 0.7% to 0.8%.20 So, is Mirova’s optimism untainted despite the gathering clouds? The answer is yes! But the trends will be far less spectacular than those of the last six months.

Many indicators still set to ‘go’

The global economy is still benefiting from a gradual and sometimes uneven easing of inflation, allowing a return to growth in real household income, as well as very dynamic activity in services and fiscal policies, which are still accommodating just about everywhere in the world. Businesses also remain highly profitable overall, keeping employment and investment afloat. Another positive factor is the rebound of the global manufacturing cycle, with the restocking process beginning to support industry, and gradual recoveries in countries that have suffered, such as Germany.

Disinflation has thus enabled a number of central banks to begin cutting rates, as in Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, the Eurozone and several emerging countries. The balance now favours central banks that are cutting rates over those that are raising them, a trend set to continue in the coming months.

On the markets, the trend was marked by a hyperfocus of performance within the largest indices, notably the Magnificent 7 in the US, gradually narrowing to 5 technology stocks, leading with Nvidia. The US market, of which these 5 stocks represent more than 25%, accounts for just under 2/3 of global indices.20

Nevertheless, the political/geopolitical agenda poses a downside risk to activity in the second half of the year. Half the world’s population is due to go to the polls this year, and each election has so far triggered stock market declines, as we saw in India, the Eurozone and especially France in the wake of the dissolution of the National Assembly. This last has rekindled fears regarding the fiscal policy France will adopt, with a possible (probable?) worsening of the deficit.

Political tensions may increase on the other side of the Atlantic as well, at least until the presidential elections in November. This race also raises fears of a runaway debt crisis in the United States, if the manifestos of the two candidates are anything to go by.

Over the next six months, political issues will undoubtedly remain at the centre of attention, even though the geopolitical tensions of the first half of the year—Ukraine/Russia, the Middle East and China/Taiwan— have so far had only limited repercussions on the markets. Coupled with signs of a slowdown in growth, there is every chance that the coming period will be a more turbulent one for the markets, while maintaining a positive bias. We do not anticipate a sharp correction, however, as growth remains positive and the expectation of rate cuts by the main central banks may yet bear fruit, but we do expect a market with higher, slightly bullish volatility, calling for a high degree of tactical finesse.

Europe : « it’s politics, stupid »

Europe’s first half proved an upside surprise, with a rebound in exports and a slight recovery in consumption. Households saw an improvement in real income, thanks to continued disinflation, a solid job market and wage increases. Consumer confidence improved, and the large savings reserves hold out hope for a positive second half of the year, especially as financial conditions are beginning to ease, an aspect that should become more pronounced with future rate cuts by the ECB.

Could this dynamic be hampered by the political upheavals in France? We don’t believe so at this stage. Admittedly, political uncertainty could prompt households to return to savings reflexes, paired with a freeze on investments. Such a wait-and-see period would cost French growth a few tenths of a percentage point. But it is difficult to extrapolate beyond the nation’s borders in the short term.

As regards France’s debt trajectory, these elections highlight some of the country’s vulnerabilities, and the—al-beit remote—possibility of a showdown with the European Union if the Left alliance were to successfully insist on implementing an aggressively expansionary fiscal policy, with negative consequences for the OAT-Bund spread. A coalition lacking a majority would block major reforms in favour of more consensual areas, at a time when the EU is calling on France to find tens of billions of euros in savings by the end of 2025. The next major event to be scrutinised by the markets will be the next government’s budget, to be presented in the autumn.

We therefore believe that the market’s assessment of the French deficit will depend on the direction of public investment and spending. If the latter are used to prepare for an increase in potential growth, by focusing on sectors such as innovation, transition and infrastructure, a deficit above the 3% threshold might be tolerated for a few more years.21 Otherwise, the market could take umbrage. Meanwhile, we note that the political programmes favoured by France’s elected representatives seem to favour current expenditures rather than such investments.

RUNAWAY DEBT AND CONTAGION: THE WORST-CASE SCENARIO

The worst-case scenario, to which we do not subscribe, would involve an inability by the French government to stabilise the debt/GDP ratio, leading to a debt crisis and contagion. The Commission has placed 7 European countries under debt surveillance, which would likely be among the first to fall, notably Italy, the largest net recipient of the European budget. France, on the other hand, remains—so far—the second largest contributor to this same budget. As for Germany, it would be precluded from coming to the rescue of the other Member States, with political resistance on this issue growing within the current government.

UNITED KINGDOM, AN ISLAND OF TRANQUILLITY

The United Kingdom seems to be starting a new cycle. It is finally coming to the end of the Brexit episode, the political and economic repercussions of which will be felt for several years and several governments. As expected, the elections brought to power the Labour Party, which has no ties to Brexit. The country could now be seen as an island of stability.

United States: ‘it’s the economy... and politics, stupid!’

After an exceptional end to 2023, the US consolidated its gains in the first half of this year. However, a number of less favourable signals have since emerged, of a sort likely to justify rate cuts by the Fed in the next few quarters to prevent them from gaining momentum as 2025 approaches.

First to note is the fragile state of low- and moderate-income households, as reflected in increasing consumer and car loan defaults. Despite a resilient job market, these households are being penalised by persistently high prices and very expensive rents. High-income households, on the other hand, have benefited from buoyant asset prices, led by equities and property, so that they have not felt the same effects, at least not to the same extent. While this has been very positive for the US economy, it also raises the question of its dependence on financial asset prices.

In the second half of 2024, attention will be focused on the property markets. With the new-build market slowing due to high interest rates, there has been a massive shift to the rental market, which is unable to absorb demand, resulting in high rents that are penalising households. To unjam the market and put an end to rent inflation, it could be useful for the Federal Reserve to lower its rates, in order to unblock transactions and construction. The paradox is that, while the Fed has been able to break the inflationary spiral in most current goods by raising rates, it is by lowering rates that it can best achieve results in the most essential sector where inflation is holding out: housing.

The influx of migrants to the United States helped to fill a significant need for labour after covid, boosting productivity in certain sectors and supporting consumption. However, the pressure it is putting on rents and the concerns of some Americans are now making it a major campaign issue for both candidates. This complex issue is a reminder that the country is confronted with contradictory signals at several levels of its economy. Industrial production rebounded at the end of the first half of the year, stimulus plans continue to stimulate the economy, the employment situation is returning to normal, but the Fed’s higher-for-longer policy is beginning to have a noticeable impact on consumer purchasing power. Not to mention the fact that a large proportion of the population is heavily exposed to the equity markets and would suffer from a downturn.

All in all, we expect US growth to continue its slowdown, converging rapidly towards its long-term trend (2%22 real annualised growth). We also anticipate continued disinflation thanks to a gradual deceleration of rents and wages as rebalancing of supply and demand in the labour market takes place in the background, and the start of a cycle of Fed rate cuts this autumn ahead of the presidential elections, although these could quickly come up against the candidates’ programmes.

TWO PROGRAMMES AND A CONCERN ABOUT DEBT

The programmes of presidential candidates Joe Biden and Donald Trump make no provision for fiscal consolidation, suggesting instead a public deficit of around 6% to 7%22 of GDP. The cost of debt would be 3%22 per annum, with a negative primary balance. The policies as currently announced would be inflationary, nudging interest rates upward. In theory at least, this could rule out some of the Fed’s 2025 rate cuts.

While the candidates’ programmes are similar in this respect, they differ on a great many points. Joe Biden would prefer to beef up social spending, which would increase the deficit. He would also begin to raise taxes on businesses and high-income households. Donald Trump, on the other hand, has stated his desire to reduce the trade deficit and immigration, and to continue his policy of tax cuts begun in 2017. Curbing immigration could have inflationary consequences, or even break the growth momentum. Imposing a 10%22 tariff on all imports, including those from Europe, would inevitably affect the purchasing power of Americans. On the other hand, this choice could avert the risk of overproduction weighing on the US economy. Donald Trump would not require Congressional approval for decisions on immigration and trade policy, however, Congress must be consulted on the extension of the Tax and Jobs Act. If Trump wins, we can expect higher rates on the long end and a steeper yield curve.

Central banks in the driver’s seat

The Federal Reserve is likely to make its first rate cut in the second half of the year, as the economy shows signs of slowing and the only truly persistent component of inflation is rents (see above). Our central scenario is for the economy to slow over the summer and for a rate cut to be announced in the autumn, probably followed by another before the year’s end. In short, a more dovish stance than the market.

In Europe, unfavourable base effects will make it impossible to swiftly achieve the 2% inflation target.22 That said, no acceleration is expected, especially as wages continue to normalise. A first rate cut by the Fed would also support the ECB in its own easing cycle. On the other hand, if the Fed fails to act, the Eurozone will suffer from imported inflation due to a weaker euro. Among the remaining risks are also political/geopolitical uncertainties and their consequences for consumption, as well as a looming debt crisis if the budgets of the major European countries—no-tably France—are not brought under control. Further evidence that the political component could influence the ECB’s decisions. After the 25bp22 cut in June, we are expecting two further cuts between now and the end of the year, in September and December.

In Japan, the central bank is keen to normalise its interest rate levels (upwards) but will proceed cautiously as there is no certainty that long-term growth will lead to a sharp rise in real wages, as the weak yen is generating imported inflation.

China has enough room to make further rate cuts to support its property market and credit momentum, especially as the country is not worried about a depreciating yuan, given that its economy is based on exports. Inflation re-bounded slightly in the first half of the year, but is expected to remain contained between 1%23 and 1.5%23 in the second half due to falling energy prices and resistance to change in food and service prices.

China and emerging countries face a more protectionist world

In the second half of the year, China will have to continue seeking new engines to drive growth, while the property crisis has yet to retreat into the rearview mirror. Prices are still in the process of correcting, and local government debt has exploded. One possible solution would be to centralise this debt at government level or force local institutions to buy up unsold housing stock to support prices. The situation continues to weigh on household morale, with a negative wealth effect. The contraction in property prices, construction and investment is therefore ongoing, fuelled from a structural point of view by unfavourable demographic trends. The country is also engaged in overproduction, at a time when the world’s borders, notably in the United States and Europe, are less open to China.

Nevertheless, fiscal and monetary support is effectively bolstering the country’s economy, with industrial output exceeding expectations. Inflation should continue to climb in the second half of the year, rising above 1%23 causing the spectre of deflation to recede. Composite PMIs24 are in line with annualised growth of up to 5.5%23 for 2024, before slowing in 2025. In the first half of the year, the PMI indices hit the highest levels seen in a year for services and two years in manufacturing. We therefore do not believe that there will be a recessionary shock, or a sudden worsening of the property market that would drain the possibility of growth over the next 18 months.

We should now expect increased competition among the countries of South-East Asia. Western countries have embarked them in their respective diversification strategies, while India is stepping up its exports of semi-finished products. India re-elected Narendra Modi as its new leader this spring, albeit without an absolute majority. His objective will be to continue the country’s development. The country is becoming increasingly powerful in industrial terms, and has succeeded in securing stable energy and raw materials imports. India now serves as a staging post for investors moving away from China.

India’s growth is pulling other South-East Asian countries in its wake, which are doing better than expected. Korea, Indonesia and Taiwan are all experiencing a rebound, and are also benefitting from the upturn in the semi-conductor cycle. All this makes Asia look like an area of growth and interest for investors.

On the markets, EMs25 disappointed in the first half of the year, mainly on equities, but to a lesser extent on debt. They should now benefit from a normalisation of Fed policy and a possible flattening of the dollar.

Conclusion: too quiet a second half?

By way of conclusion, we have little in the way of iconoclastic notions to offer our readers: the soft landing unspools gently in the second half of the year, with inflation easing to levels higher than before Covid... giving central bankers a good chance to lower rates made all the more probable as this may unlock rents in the United States, where they represent the last major enclave of inflation.

Beware, however: 2025 could turn out more tumultuous, as Mr Biden and Mr Trump seem determined, each in their own way, to add fiscal expansionism to economic expansion. As we see it, there is thus no point in waiting for a rate-cutting cycle as marked as those of the past, something the market will begin anticipating as early as the months ahead.

The long view

Crisis of the Western middle classes: is the worst over?

As noted in our editorial, Mirova is concerned by the disenchantment of the western middle classes, which have been central to economic growth and improvements in living conditions, albeit not without issues, since the end of the 19th century in Europe, English-speaking North America, Japan and, more recently, South Korea. This discontent not only signals the likelihood of current economic dysfunctions, but above all has the potential to weaken a framework favourable to prosperity. However, as everyone finally recognises the problem it is doubtless already approaching its acute phase, if indeed the paroxysm has not already taken place.

The election of Mr Trump in 2016, Brexit, the vote in favour of M5S followed by La Lega and the Fratelli d’Italia in Italy, Vox in Spain, Vlaams Belang in Belgium, the PVV in the Netherlands or the AfD in the East German Länder, the parties furthest to the right or left of the French political spectrum... all this clearly spells out that Western societies are no longer functioning well enough, at least not for enough of their members. Take the detailed analyses that have sought to explain where these votes originate, their more-or-less structural nature, the social classes or age groups that fuel or hinder them, the demographic changes allegedly accelerating these dynamics. All point to a rejection of the usual political options, which seem—rightly or wrongly—to no longer address the problems experienced by many socio-professional categories, particularly those far from the bustle of metropolises: Washington D.C. voters readily share the views of Parisians, Londoners or Milanese, but are confounded by those of their fellow citizens, so close geographically but so far removed from their daily lives.

These myriad issues could be construed as strictly political, with perhaps a vague sociological or economic backdrop, and therefore of no concern to finance or the markets. However, because they are responsible for allocating capital to some projects and economic infrastructure at the expense of others, and because they influence our social organisations, which shape them in turn, investors play a pivotal role in what is happening, for two reasons. Firstly, finance has nothing to gain from a collapse of the highly favourable system in which it has been operating, sometimes without realising it, for almost a century and a half. Placing finance and the markets at the service of the middle classes? Not such an irrational wager... quite the contrary.

THE EVAPORATION OF THE MIDDLE CLASS: A DAMPER ON DEVELOPMENT?

The feeling of being downgraded experienced by an ever-wider spectrum of western populations poses a threat to the stability of democratic systems, which are in and of themselves conducive to creating the conditions for prosperity. The situation is more a reflection of this erosion of prosperity than its cause, however one does not prevent the other: the two are now mutually reinforcing. That the process takes the form of increasingly radical voter positions signifies that the middle classes can no longer tolerate a situation they feel they have been pushed into against their will.

For a long time they demonstrated considerable patience in the face of a declining median and average incomes, particularly in the United States, to say nothing of effects such as the fall in life expectancy for entire segments of the American population or the deterioration of infant mortality. Other indicators bear witness to the unfavourable winds buffeting the middle classes. For the sake of comparison, in the 1970s, the wealthiest 1%26 of the US population represented less than 10%26 of aggregate national income; by the mid-2000s, they accounted for a quarter! Differences in wealth obviously exacerbate those in income, but this is largely due to the fall in interest rates, which has increased the value of property and therefore the wealth of owners, without any additional value creation per se, excluding transactions.

The sense of belonging to the middle classes began to decline almost 25 years ago: more than two-thirds of Americans felt they belonged to the middle classes at the end of the 20th century, versus less than half in 2012, according to data from the World Value Surveys. There are two reasons for this: the (at best) stagnant real income of the so-called middle classes, and the rise in cost of living attributable to soaring property prices, which drops in the price of everyday consumer goods has not meaningfully offset.

Mirova will restate it once more: if the world of finance imagines it can carry out its functions smoothly under a political framework unacceptable to the working classes, it commits a sin of wilful ignorance with far-reaching consequences. The financial markets as they have existed since the end of the 19th century have never been compelled to operate in such a configuration for long and, in our view, would be hard pressed do so.

To put it plainly, finance must ensure it preserves the framework that allows it to function fairly optimally, albeit imperfectly: the democratic framework, which cannot continue without the support of the middle and working classes. This is not a moral principle, but a rational one. At present, finance possesses the means to help restore this framework at the very moment when its deterioration no longer seems bearable, provided that it allocates capital to activities that can forestall the weakening of the middle classes.

RE-INDUSTRIALISATION: YOU DIDN’T KNOW, BUT IT’S ALREADY HERE...

Some of the conditions for resolving the torments of the middle classes are emerging on their own, even as we write. Re-industrialisation and the almost completed rise in interest rates (the latter partly a result of the former) are, paradoxically, ushering in highly favourable prospects. North America is already reaping the benefits, as witness the over $100 billion27 drop in the value of imports from China in 2023.28 This was not solely due to the Biden admi-nistration’s clever Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). However, it should be noted that it is easier to achieve such results in North America, where the industrial employment rate remains lower than in Europe, and which has access to a large pool of raw materials that, unfortunately, the old continent does not possess.

As a quick reminder: in 2009, more than half of the world’s middle-class population lived in North America and Europe, according to the OECD, which adds that by 2030, this proportion will have fallen to around 20%.27 That’s a 30 percentage point drop over just 30 years, no less. Meanwhile, Asia’s contribution to the middle classes is set to rise from 28% to 66%27 over the same period. How did this shift come about? The gradual transfer of industrial production capacity from the West to China since Deng Xiao Ping opened the doors wide in the early 1990s. However, this mechanism now seems to have slowed or even ebbed since Presidents Obama and then Trump began to question the nature of exchanges with Chinese producers, a policy President Biden has done little to change and which we believe the next occupant of the White House, whoever that may be, will not question. Europe seems to be following a similar path, despite the reluctance of German manufacturers, who have become highly dependent on the Chinese market. We should add that China, while now an ageing country, no longer conceals that it has less need of Western inputs than it did 30 years ago, now that the West has supplied it with the techniques and technologies it wanted to master, and which it now wields better than anyone in some cases.

It is therefore clear to everyone that the ambition of repatriating production capacity westward can only be a long-term objective. If it comes to fruition, it will boost the supply of jobs at a time when demographic trends are bound to push wages upwards, unless we accelerate migration flows to satisfy these offers and balance labour supply and demand, or unless the combination of artificial intelligence and robotics provides the necessary labour capacity. Yet the trend has already begun, in the United States, but also in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia: Poland, Denmark and Sweden have all seen sharp rebounds in industrial production since the Covid crisis. More recently, Ireland has recovered very briskly. Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and, to a lesser extent, Italy, on the other hand, remain in decline, with industrial output still at half-mast.

Another favourable factor, and a paradox, is that the pressure exerted by rising interest rates on property prices should make it easier to access housing after a few difficult years caused by the fall in construction volumes, particularly for younger people. The wealth effect will certainly suffer, but with a lesser impact than before, as the generation that will absorb it gradually reaches an age when the level of consumption per household fades. In France, for example, the demographic group with the highest proportion of homeownership, nearly 75%29 is people over 70.29 The same is true in the United States, where over the last twenty years, only the over-65s have seen an increase in their share of homeowners, while the proportion for all other age groups has fallen, in some cases spectacularly.30

The return of well-paid industrial jobs and the easing of the property burden that has become untenable for young people over the last thirty years together form the basis for reviving the middle classes, which will be able to patiently rebuild a more stable political consensus and contribute to an economy with lower income inequality, and therefore a greater likelihood of prosperity. Add to this the fact that reindustrialisation of this kind will fit seamlessly with environmental transition, given that the carbon footprint in Europe and North America remains lower than China’s for equivalent production, notably by reducing sea or air transport. If reindustrialisation contributes to avoiding both a social crisis and the undesirable effects of a climate change-induced crisis, why didn’t it start earlier? Co-vid served as a trigger for the movement, as did geopolitical rivalries, but of course industrial investment involves long-term decisions: moving capacity to Asia took almost forty years; it is natural that bringing it back to the West will take at least a decade.

THE FUTURE LOOKS BRIGHT, SUBJECT TO CERTAIN CONDITIONS

Is everything for the best in the best of all possible worlds? Certainly not. There remains a major stumbling block: levels of debt, particularly public-sector debt, are generating deficits that set peacetime records, and the ageing of the Western population, which, while mitigating the negative wealth effect of rising interest rates, creates problems of its own. These two disruptive factors can, however, be absorbed by a return to productivity gains. This is already happening in the United States, which would also have plenty of fiscal room for manoeuvre if necessary... particularly if Mr Trump or Mr Biden were to pursue expansionist fiscal strategies at a level too aggressive for the dollar, forcing them to change their policies. The capacity of the United States to once again generate budget surpluses, as it did at the end of the second Clinton administration, still exists in theory, despite a current federal deficit exceeding 6%31 of GDP. Western Europe, on the other hand, has access to neither of these levers currently. Productivity gains have yet to materialise...

This is where the world of finance has the most crucial choices to make when it comes to allocating capital to productive investment, because political leaders cannot undertake this alone. The rise in interest rates has implicitly served a purpose: to increase the return on these productive investments, at a time when property has ceased to monopolise a significant portion of the capital stock and energy needs, two resources without which industrialisation is impossible. For Europe, as for India, some of this energy must come from renewable sources. Impact Finance aims to promote the prosperity of its clients and collective prosperity by allocating capital only to those agents that do not present a threat, and there are many. Finance that does not take these criteria into account could achieve the same objectives, but it would be less likely to succeed.

In short, while the impatience of the middle classes may appear to herald the worst, i.e. the collapse of Western societies and democracies, the reorganisation of globalisa-tion on terms more advantageous to the West than those of the last ten years could well prevent this sad scenario from becoming reality. This reindustrialisation has in fact already begun, and will unfold in its own time, spreading its positive effects over a decade. The worst, it would seem, is never a sure thing.

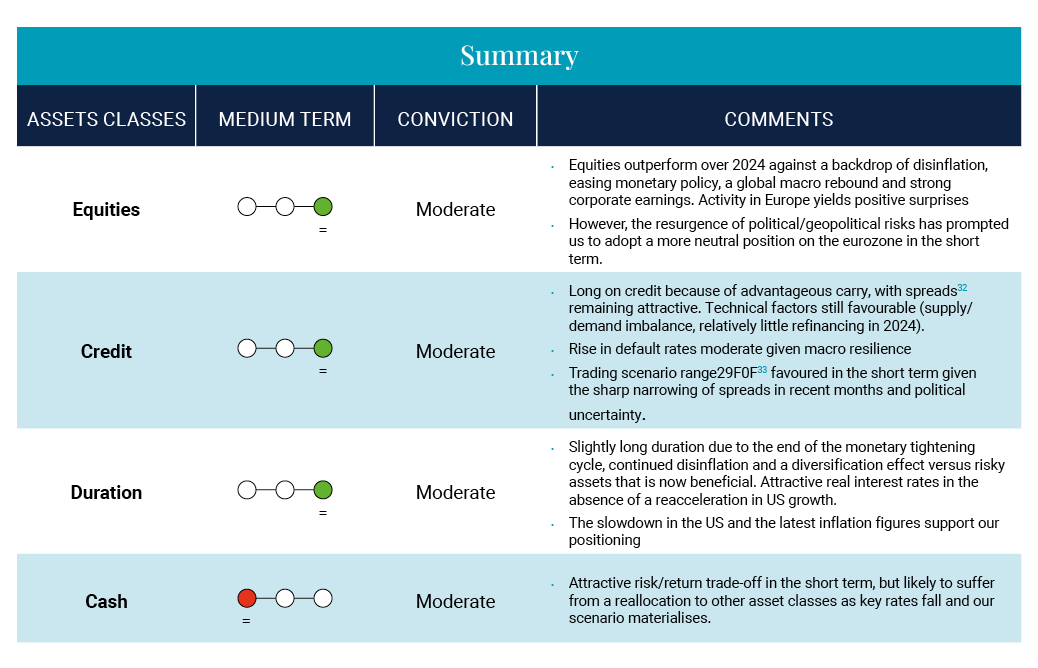

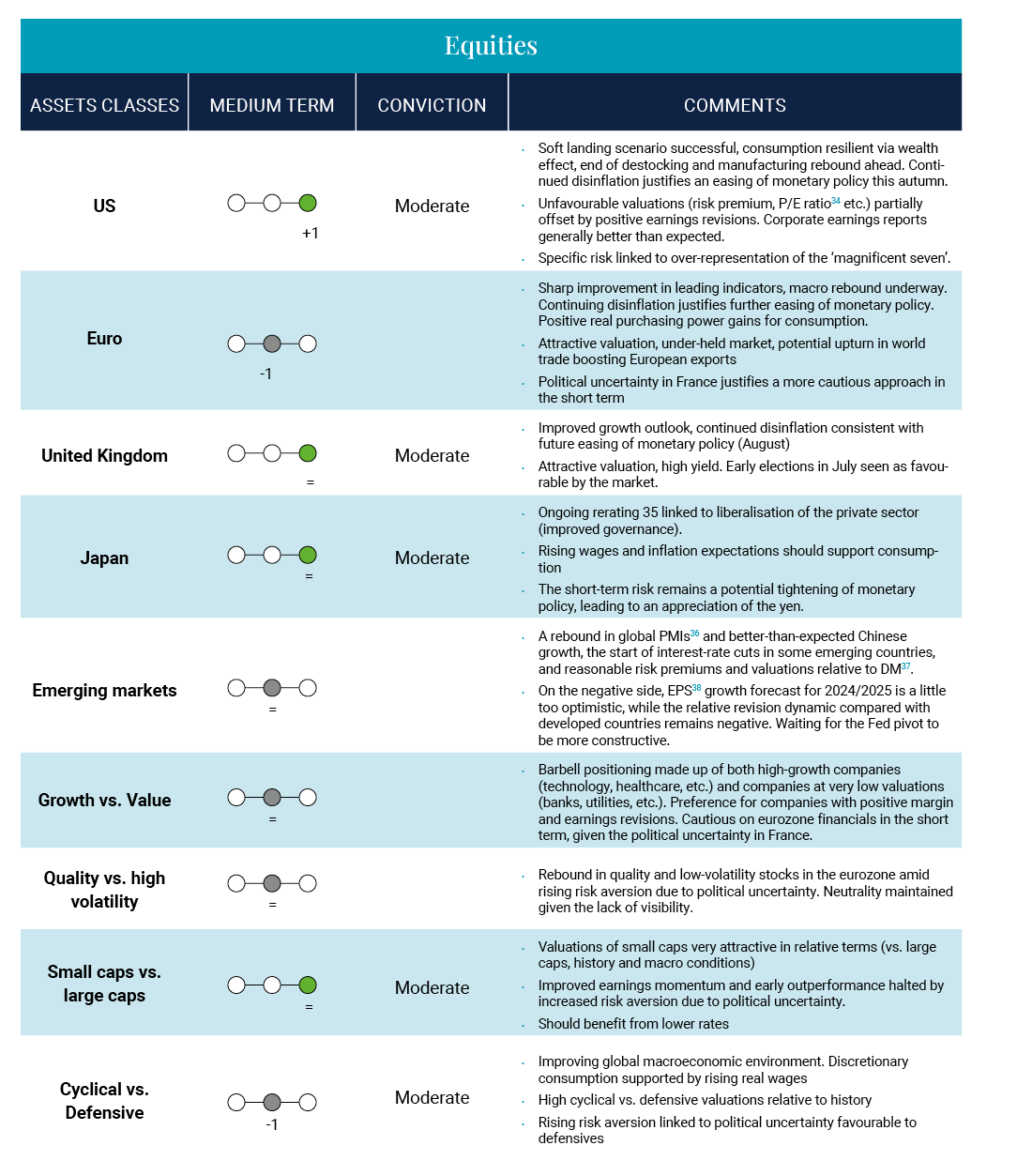

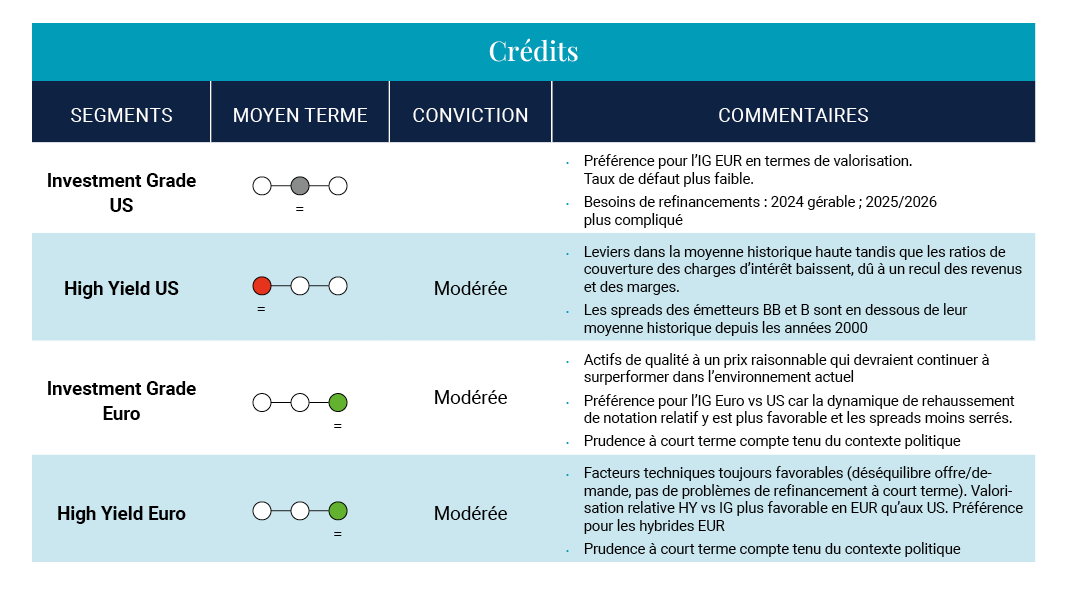

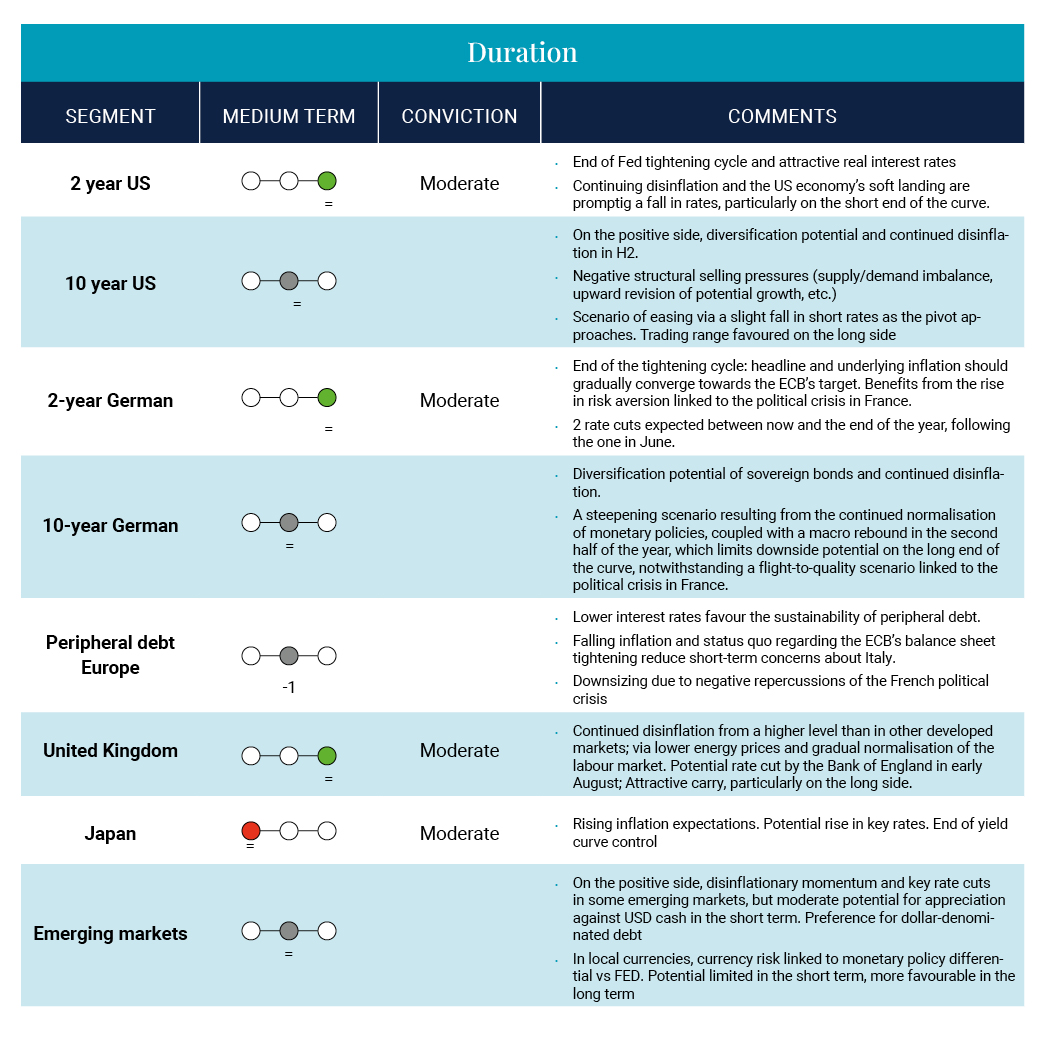

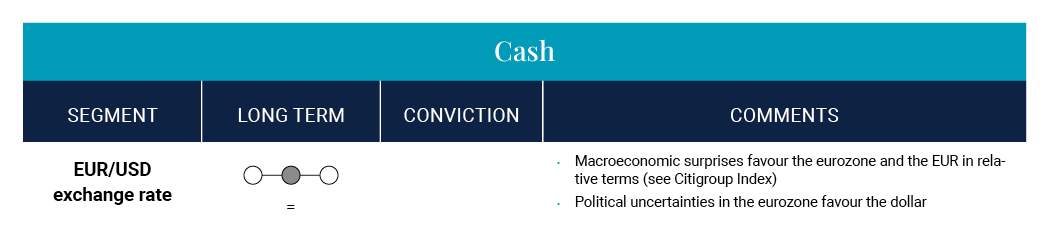

Summary of Market views

1 French obligations assimilables au trésor, or fungible Treasury bonds

2 To the point at which something makes no sense

3 Gross domestic product

4 Source: Bloomberg

5 European Central Bank

6 US Federal Reserve Bank

7 Source: Bloomberg

8 Bank of Japan, Japan’s central bank

9 Source: Bloomberg

10 Earnings per share

11 The S&P 500 is a stock market index based on 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States

12 Price to earnings ratio

13 Source: Bloomberg

14 Artificial intelligence

15 An ETF (or tracker) is an investment that tracks the performance of a stock market index (CAC 40, Nasdaq, etc.).

16 High quality asset according to ratings agencies

17 Very small enterprise

18 Very small industry

19 Source: Bloomberg

20 Source: Bloomberg

21 Source: Bloomberg

22 Source: Bloomberg

23 Source: Bloomberg

24 An economic indicator which combines data from the PMI manufacturing and services indices to provide a more complete and global view of economic activity.

25 Emerging Markets

26 Source: Bloomberg

27 Source: Bloomberg

28 Source: Kearney

29 Source: INSEE

30 Source: US Census Bureau

31 Source: Bloomberg

32 The spread is the difference between the two prices of an asset in the financial sector, namely the price at which a security is presented for sale, and that at which a buyer offers to purchase it, respectively the ask price and bid price.

33 The Trading Range is a relevant market indicator, particularly for stochastic indicators.

34 Indicator used in financial and stock market analysis.

35 Re-estimation

36 Purchasing Managers’ Index

37 Developed Markets

38 Earnings per share

The information given reflects Mirova's opinion and the situation at the date of this document and is subject to change without notice. All securities mentioned in this document are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute investment advice, a recommendation or a solicitation to buy or sell.