Mirovα, Creating Sustainable Value - November 2024

Monthly market review and outlook

October: waiting for Trump and Powell

When everything’s going right, it all goes wrong: better-than-expected US statistics, combined with the prospect of Donald Trump's victory, led to profit-taking on the equity markets at the end of October, as investors feared that this would put the brakes on the Federal Reserve's long-awaited interest rate cuts. As a result, interest rates rebounded sharply and bond markets plunged, with global bonds recording their worst monthly performance for two years. We have not seen downturn like this since 2022, when the Fed announced an interest rate hike of 75 basis points1 to counter runaway inflation.

In October, for example, US Treasuries shed 2.5%1, corresponding to an increase of around 50 bp1 on the 10-year yield. Investors are now anticipating the Fed2 to set a terminal federal funds rate of around 3.5%1. A month earlier, they were still expecting a rate of 2.9%1 and have thus erased more than 2 potential drops in the space of a few weeks. The likelihood of Trump and his party winning the presidency and both houses grew steadily until the election, leading to a rise in the levels of inflation implied by the market. The Republicans' tariff, migration and economic support policies are seen as more inflationary than those of the Democrats.

At the same time, US GDP3 growth in Q3 remained solid at 2.8%1 on an annualised basis, driven by strong domestic demand. The employment market came as a positive surprise, with the latest employment report at the beginning of October showing a low unemployment rate of 4.05%1 and a significant acceleration in payrolls in September, with 220000 jobs created. Consumer confidence has also risen sharply, according to the Conference Board index, and the disinflation trend seems to have come to a halt, with the core CPI4 at 3.3%1.

There are therefore both economic and political reasons for the upturn in US interest rates.

In the UK, bondholders also suffered as the budget announced by the government in October turned out to be more expansionary than expected. More borrowing over the next few years and significantly higher growth and inflation expectations for 2025 have pushed the UK 10-year yield to 4.44%, up 44 bp1 over the month. The spread with Germany widened to over 200 basis points, a 2-year high. In the eurozone, by contrast, sovereign bonds "only” lost 1%1. The ECB5 cut its key interest rates by a further 25 basis points as business confidence fell for the fifth consecutive month and forward-looking indicators remained weak, pointing to downward pressure on the employment market. Headline inflation is moderating, with an October figure of 2%1 y/y, and core inflation is stabilising at 2.7%1 y/y, driven by a services component which is still higher than expected but which should gradually normalise.

Equity markets, affected by the upward movement in interest rates, also ended the month in the red. The S&P5006 lost almost 1%1 - its first fall for 6 months - and the Stoxx 6007 posted its worst monthly performance ever, down 3.5%1 year-on-year.

These contrasting performances should not detract from the good start to the results season. More than 2/3 of US companies have already published their results, and they have come in well above expectations, including technology companies, which continue to delivergood news...

In Europe, the reporting season is less advanced at this stage, but trends are more mixed for the time being. Most companies have published results in line with expectations, and downward revisions are continuing in sectors with the greatest exposure to China (notably cars, luxury goods and commodities).

Another major theme in October was geopolitics, as tensions in the Middle East remained high, with the market fearing a flare-up in the conflict between Israel and Iran. The price of oil, up 2%, 8continues to fluctuate in line with the varying degrees of retaliation from each party.

Against this backdrop, assets perceived as safe havens performed strongly. The dollar, benefiting from Trump trade, gained 3.2%, its biggest monthly rise in two years, and strengthened against all the other G10 currencies. It was also a good month for precious metals, with gold up by more than 4% to an all-time high at the end of October.

Graph of the month

Macro review and outlook

Macroeconomics: the start of a new era?

Following the outcome of the US presidential election, a new phase has begun: that of questioning the impact of Donald Trump's policies on the US and global economies. These effects will take several months to be fully felt. In the meantime, the United States should end 2024 on a positive note, with a highly resilient economy. In the eurozone, the figures came in slightly above expectations, but the fragility of certain countries, such as France and Germany, cannot be overlooked. Lastly, China deserves a close look, between the positive signs of fiscal stimulus and future tensions with the United States.

United States: remarkable resilience

US GDP grew by 0.7%9 in the third quarter, or 2.8%9 on an annualised basis, and is benefiting from solid underlying trends. Consumer spending is proving resilient, with annualised growth of 3.7%9. They are benefiting from the confidence of consumers, who are enjoying a wealth effect thanks to real wage increases and the good performance of the stock market and property. It is worth noting that, while consumption has been strong so far, the average amount of cash held by US consumers at the end of Q3 could be underestimated and will remain above pre-pandemic levels adjusted for inflation, according to various sources such as JPM, Bank of America Institute, etc. . The focus is more on the employment market, where recent developments have been more mixed. Net new non-farm payrolls (NFPs) were only 12,0009 in October, due to the hurricanes and strikes (Boeing, dockers) which made interpreting the data difficult, while the figures for the last two months have been heavily revised downwards.,In addition the vacancy-to-application ratio at 1.099 is now hovering around pre-covid levels and the resignation rate is at its lowest for 4 years. The employment situation is therefore in the process of normalising, even though it remains healthy overall, with a historically low redundancy rate. The unemployment rate remains stable at 4.1%11.

Inflation is continuing its very gradual decline. PCE Core inflation10 rose by 0.25%11 in September, to an annualised rate of 2.3%11 over the last 6 months. The super core services component of the latest CPI12 is also moderating, in line with the slowdown in wage growth and productivity gains seen in recent months.

The context does not alter the Fed's trajectory for the time being, which, after a further rate cut at the beginning of November, is expected to lower rates by 25 basis points in December. This normalisation is likely to continue under Donald Trump's presidency, albeit at a slower pace and with a downward target that may be less ambitious given the inflationary nature of part of Trump's programme (higher tariffs, reduced migration flows, lower taxes, etc.). It will therefore take time for these policies to be implemented and have an impact on the economy. And everything will depend on the government's priorities. If the emphasis is placed more on policies to deregulate the economy and improve the efficiency of public spending and less on inflationary policies, the consequences for the Fed's monetary policy will be quite different. Finally, Trump and his team can ill afford a significant rebound in inflation in the short term in the eyes of their voters, most of whom are middle class and very sensitive to their purchasing power.

All in all, the US should record growth of 2.8%11 over 2024 as a whole and, barring any major exogenous shocks, could continue to outperform consensus expectations without generating any real inflationary pressures. The partial or non-application of Trump's tariff and migration policies and continued productivity gains will be key factors.

Eurozone: a fragile economy and political uncertainties

The 0.4% growth recorded in the eurozone in the third quarter, or 1.5%11 annualized, was a pleasant surprise. Spain is still holding its own, with growth of 0.8%11 and buoyant consumer, energy and tourism sectors. The situation remains okay in Italy too, despite zero growth due to the weakness of its industrial sector. In France, the Olympics effect is being felt, with growth of 0.4%11, which will fall back in the final quarter. Germany, with growth of 0.2%11, has ruled out the risk of a technical recession. The composite PMI indexes for the region are at 50, with services PMI even reaching 51.711.

However, the eurozone continues to face a number of challenges. France is facing budgetary uncertainty and will have to reduce its public spending, while growth is still showing no sign of sustainable recovery. In the eurozone, the manufacturing sector is still struggling, penalised by a lack of prospects. Exports are generating only limited gains, which are likely to weaken further as a result of the new US tarrif policy. What's more, companies are still cautious about investing in this uncertain political climate, and labour costs are high without any real gains in productivity.

The employment market is also showing signs of weakness, with the start of a decline in services in Germany and France, while the manufacturing sector is beginning to shed jobs. This creates additional risks for domestic demand, which is a major pillar of support in an otherwise sluggish economy. The latest unemployment figure was 6.3%11.

In October, inflation rose to 2%11 after having fallen to 1.7%11 in September due to base effects. Core inflation remained stable at 2.7%11, without causing any concern. We expect disinflation to continue. The weakening of the employment market and weak growth should justify the ECB continuing its monetary easing until the summer of 2025, with a target of 1.75%11 for its terminal rate. In 2024, GDP in the eurozone is expected to grow by 0.8%11, and could reach around 1%11 in 2025, although there is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding this figure due to the political/geopolitical context.

Germany: light at the end of the tunnel?

After three years of economic stagnation, Germany is heading for early elections on 23 February 2025 to break the political deadlock. The likely outcome will be a coalition of the current centre-right opposition, the CDU/CSU, with a centre-left partner, most likely the SPD. We expect a new government led by CDU leader Friedrich Merz to usher in a wave of pro-growth reforms combined with some changes to the debt brake to give the new government a little more fiscal room for manoeuvre. Unless there is a major exogenous shock (escalation of the trade war with the United States, Putin's victory in Ukraine), the German economy should begin to recover from spring 2025 onwards.

United Kingdom: a budget to finance the future

Borrowing to pave the way for tomorrow's growth: that's the thrust of the plan presented by the British government. The plan came as a surprise but seems to have been well received by observers, unlike the one announced by Liz Truss just two years ago, which led to her resignation amid a bond crash. What is notable this time is the commitment to long-term structural spending, with priority given to education (£7 billion13), health (£22 billion13) and infrastructure

To finance this expansion of public services, the government plans to gradually increase tax revenues through a series of tax hikes, such as an increase in employers' contributions or capital gains tax, but also plans to borrow more on the markets, to the tune of a further £30 billion13 next year. This plan to increase public spending should create 0.2%13 to 0.3%13 additional GDP growth from 2025. Businesses and households should also be pleased to have a clear roadmap for tax rises, which could pave the way for a recovery in investment and consumption.

This should also tighten the employment market and could generate a little inflation. Enough to convince the Bank of England to slow down its programme of interest rate cuts next year.

Chinese slight upturn

The fourth quarter could see a rebound in Chinese growth. The effects of monetary and fiscal stimulus are beginning to be felt. The manufacturing and services PMIs rose slightly above 50, and new house prices rebounded slightly, as did consumer spending.

Although deflationary pressure remains, as does high youth unemployment, the macroeconomic situation is stabilising and the Bank of China announced a further rate cut at the end of October. The main uncertainty for 2025 concerns Donald Trump's trade policy. Faced with an increase in US tariffs, China could choose to let its currency depreciate, support its economy through a massive fiscal stimulus package - and turn to a European market that is less reluctant to open its doors. Since Trump's election, the government has been content to approve a 10 trillion yuan programme to restructure local government debt.

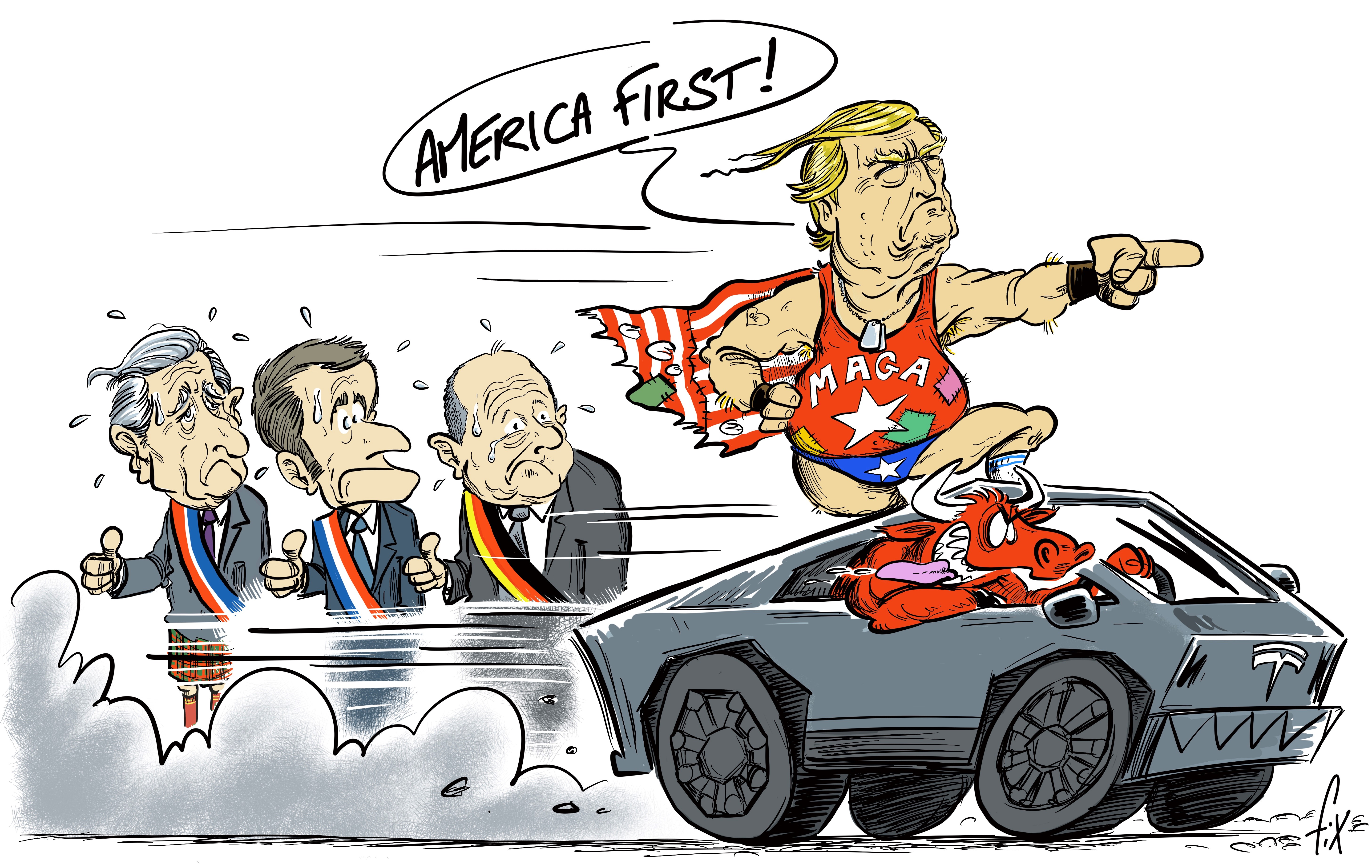

A new presidency for Donald Trump

To what extent will Donald Trump be able to implement the programme presented during his presidential campaign? Here are some of its main promises:

- Economy: extension of the tax cuts enacted in 2017 which expire at the end of 2025, new tax cuts in particular for companies, measures to deregulate and cut the federal budget

- Trade: trade tariff war this time covering all imports, intensification of technological restrictions against China

- Immigration: mass expulsion of illegal workers

- Geopolitics: rapid resolution of ongoing conflicts (Ukraine, Middle East)

There is no doubt that the increase in customs tariffs alone will not be able to finance the tax cuts announced for businesses and households, hence the desire to reduce public spending, a mission apparently entrusted to Elon Musk.... Will tariffs be raised at the same time or will they be subject to negotiation? What will be their scope and timetable?

One thing is certain: their impact on the real economy is unlikely to be felt before the end of 2025, but the resulting rise in prices would be very unwelcome by voters.

The uncertainty surrounding tariffs and potential retaliatory measures by the countries affected could also generate economic uncertainty and lead some companies to scale back their investment and hiring plans.

Similarly, excessive restrictions on migratory flows would lead to labour shortages, just as they would after the end of confinement. This would lead to wage pressures, something that companies will need to keep an eye on. These companies are providing solid support for US growth by increasing their margins. An increase in the cost of labour must not break this cycle Researchers at the Peterson Institute have also estimated that the deportation of 1.3 million illegal immigrants (which is far from the total) could add around 0.514 percentage points to inflation over two years.

The Federal Reserve will have to take this new situation on board. Initially, rate cuts are likely to continue, at least to a target rate of 3.75% or 4%14. Potential future exogenous shocks on customs tarrifs or immigration are, however, blurring the message as to the rest of its monetary policy, and this could create volatility on the markets. What we now know about Donald Trump's future policies is already having a bullish effect on the dollar. This will favour cyclical companies and small and mid-caps exposed to US growth. It remains to be seen to what extent global assets outside the US could be affected by Trump's policies and continue to underperform? In any case, we believe that many of the negative effects of his policies are already being felt. So will it be a soft or hard Trump?

Germany: political crisis of nerves; economic realisation

Is the German golden age of the early 21st century over?

Shortly after reunification with the GDR, Germany went through a crisis from which it emerged with great efficiency. It achieved this by banking on the opening up of the Chinese market following China's entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO), on growing access to Russian raw material reserves, on subcontracting to Eastern European countries with low wage costs and relatively weak currencies, and also on the ersatz permanent competitive devaluation offered by the euro vis-à-vis its Western European partners, whose purchasing power was then boosted by the euro. At the same time, the country was careful to maintain its role as a privileged ally of the United States in Europe, which, through the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), provided it with security without making it bear the entire budgetary burden. The result of this de facto mercantilist policy was twenty years of trade surpluses. They reached as high as 7.6%15 of GDP in 2015; as a reminder, Germany had a trade deficit throughout the 1970s and 1980s and until the establishment of the ECU16. Another result of this strategy has been remarkable political stability, reflected in Mrs Merkel's sixteen years in office. Unfortunately, the fine building seems to have developed a few cracks.

The Chinese market is shrinking under the pressure of the Trump and then Biden administrations, access to Russian gas has been restricted since the invasion of Ukraine, the countries of Eastern Europe, now richer and even members of the Economic and Monetary Union, are sometimes becoming less competitive, while some of our Western European partners now have high levels of debt, which their trade deficits have of course helped to increase.

So it should come as no surprise that Mrs Merkel's successor should find himself on the brink of losing power after barely three years in office, or that a populist party, which is rather confusing because it often changes its doctrine, should make inroads into the electoral landscape, as will no doubt be confirmed by the early general elections in February 2025. Worse still, perhaps, the symbol of Germany's dazzling prosperity at the start of the 21st century seems to be wavering: the car industry is experiencing difficult times.

The German car: the blow of the breakdown

Until recently, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and BMW were considered to be indestructible, the former in the European and Chinese markets, the latter two in the premium car segments worldwide. As is often the case in the automotive industry, leading players of the day can see their supremacy evaporate within a few years. Who remembers British Leyland, Europe's leading manufacturer in the late 1960s, which has since been dismantled? The big three German carmakers have not yet got to that point, but they have all issued significant profit warnings on their results in recent months, and even though BMW remains better able to avoid the worst pitfalls, they are facing a crisis that goes beyond the usual framework of a simple downturn in the car market, which they know how to manage very well. There are more structural causes underlying their current weakening.

The first source of this weakening is the implicit threat of de facto expulsion from the Chinese market, as Renault, Ford or FCA and PSA, now merged into Stellantis, had to endure in the past decade. Now that the local authorities have allowed Chinese carmakers to bypass the barrier to entry posed by the need for technical and industrial expertise in combustion engine/gearbox combinations, by imposing the de facto electrified powertrain, they now have attractive, low-cost product offerings. Even in the premium segments, they are finally succeeding in building coherent brands in the face of Mercedes, BMW and Audi, which are groping for answers, sometimes by creating sub-brands with, in our view, rather dubious potential. Chinese groups XPeng, Xiaomi, Nio, BYD and Zeekr (Geely), among a host of others, are all presenting models that are now competitive, with none of the shortcomings they sometimes displayed as recently as five years ago. Some of them even boast a certain technological edge, while others know how to adapt to the expectations of Chinese consumers.

The second source is that competition has intensified everywhere: in the United States and Europe, where the image of the robustness of German internal combustion vehicles has lost its lustre, while the rise in interest rates has made leasing contracts much less attractive than before. Worse still, in the electric vehicle segment - where sales are disappointing, but still growing - it is clear that Chinese carmakers and Tesla, and even Renault to a lesser extent and for some market subsegments, are ahead of them. The sometimes cruel failures of Mercedes-Benz's EQ range and Volkswagen's ID have shown quite clearly that German carmakers seem to be lagging behind some newcomers.

Add to this the fact that President Trump seems determined to impose taxes on imports of German vehicles - an idea he was already announcing during his 2016 campaign - and it seems that the German car industry is going through a rather dangerous storm. VW, Porsche, Mercedes and BMW and their equipment manufacturers have already reinvented themselves several times in the past. They'll have to do it again. The whole country is ready for it.

Germany: welcome back to Europe!

All the fundamentals on which German industry, including the automotive industry, has been relying on over the past three decades are weakening. Their export machine will not collapse quickly, but it will need to be reformed, as it has been so often, if Germany does not want to see production figures continue to fall. The good news is that the realisation seems to have set in: Germany was able to play on several fronts, but it can no longer do so, and it knows this. Germany also knows that the ideal scenario of a return to the previous status quo is not going to happen. On the whole, however, since the first warning shots were fired during President Trump's first term in office, Germany has had time to prepare and assess the options available. After playing the Chinese and US cards, Germany will find it in its interests to turn... to Europe. This will take time, as the population will have to accept that the country's successes over the last twenty years were not based solely on its own merits, but also owed a great deal to circumstances that are now crumbling.

This is the best way forward at present, but it has been too timidly pursued up to now, given that the institutions of the EMU17 and the European Union (EU) have sometimes served as relays for the country's mercantilist policy, which in exchange provided its partners with low interest rates. That period is coming to an end: Germany has globalised a great deal, and it needs to Europeanise. In plain English? Europe needs to achieve a balance where if there is consumption, there must be jobs, and if there are service jobs, there must also be industrial jobs.

This cannot be decreed, and requires support for a form of strategic autonomy, to which President Trump, freshly elected, will unwillingly invite the countries of the EU. More than six months ago, we had already calculated the budgetary consequences of a partial disengagement from NATO by the United States, since this was what President Trump was promising, even if it seemed unlikely that he would carry out his threat: Europe is going to have to go through this, partially. Of course, this will not be enough; we will need to add a collective project capable of uniting Europeans, instead of federalising Europe, which will have to abandon certain institutional objectives with unconvincing results so far, and replace them with concrete projects from which it has been distracted. The Draghi and Letta reports open up perspectives on artificial intelligence, innovation, access to resources, energy pricing, and so on. It is not necessarily necessary to adopt these reports out of hand, but they are part of a process of progress, which does not require institutional reforms so much as cohesion between all the European countries, which Germany is now in the process of adhering to after having sometimes been tempted to put the Community institutions it dominated at the service of its own interests.

Donald Trump, an accelerator of particularism

As a reminder, there can be no strategic autonomy without economic sovereignty, and there can be no economic sovereignty without production, and no production without energy. Europe must therefore maintain, if not accelerate, its renewable agenda. Consequently, those who believe that President Trump's return to the White House marks the end of ESG18 - while his first term paradoxically represented a buoyant period for sustainable finance in the United States - seem to us to be on the wrong track: on the contrary, the Trump Administration could well accelerate the trends, without exaggerating the scope of its measures either, unless Elon Musk does to US government institutions what he did at Twitter, which leads us to what Mirova has already pointed out: federal deficits of 6%19 of GDP are not inevitable for the US, quite the contrary. Mr Musk is talking about slashing the US federal budget by $2,000bn a year to bring it below $5,000bn19; and if he succeeded, the markets would have to avoid a scarcity effect on US Treasuries, which was so costly during the Asian crisis of 1997. Such a policy entails another risk: the negative second-round effects that such brutality will have on federal government employees, which Mr Musk and President Trump seem to be overlooking. To the point of calling into question the rise in US interest rates? Maybe so... but not just yet, as so many financial market players want to push the Trump trade further.

As for Europe, it will have to commit itself more firmly to a roadmap of which ESG will inevitably be a part, as will Asia - in particular India, Japan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam... - and this is not bad news for the economies of the countries concerned, particularly Germany, which could well find in this an opportunity to emerge more quickly than expected from the recession that seemed inevitable to Mirova. To the point of calling into question the lowering of interest rates in Europe? Maybe so... but here again, it will take time: it takes a few years to change economic infrastructures, to set up training courses and then a production base.

Summary of Market views

1Source: Bloomberg

2Federal Reserve Bank

3Gross Domestic Product

4Consumer Price Index

5European Central Bank

6Stock index based on 500 large publicly traded companies in the United States. The index is owned and managed by Standard & Poor's

7Stock index composed of 600 of the largest market capitalizations in Europe

8Source: Bloomberg

9Source: Bloomberg

10Personal Consumption Expenditure

11Source: Bloomberg

12Consumer Price Index

13Source: Bloomberg

14Source: Bloomberg

15Source: Bloomberg

16European Currency Unit

17Economic and Monetary Union

18Economic, Social, and Governance

19Source: Bloomberg

20Re-estimation

21Earnings per share.

The information given reflects Mirova's opinion and the situation at the date of this document and is subject to change without notice. All securities mentioned in this document are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute investment advice, a recommendation or a solicitation to buy or sell.

NEWS

Discover the 2024 Impact Report for Mirova Global Green Bond Fund.

Investing Insights from the Sustainable Equities Team