Mirovα, Creating Sustainable Value - September 2024

Monthly market review and outlook

US scare amid technical correction

Just one figure and everything changes: that's the take away for August. Disappointment at the number of jobs created in the US in July has rekindled fears of a recession on the other side of the Atlantic. In our view, these fears have been overplayed, given the overall state of the US economy. Helped by a lack of liquidity due to seasonal factors and a massive unwinding of carry trade strategies following a surprise rise in Japanese key rates, the VIX, the flagship index of implied equity volatility, rose to levels not seen since 2008 or 2020, in the midst of the Covid 19 crisis. It rose as high as 65%1 during trading on 5 August. Several positive signals quickly managed to halt this market movement, and the air pocket at the start of the month finally proved to be a good entry point. The market recovered all the ground it had lost and ended the month up by around 2% for the S&P 5002 and the Stoxx 6003. If we take a look at the magnitude of this correction, which we will describe as technical, it turns out to be fairly consistent with the behaviour of the European and US stock markets during the summer.

But let's return to the macroeconomic fears: if the weakness of the job creation figures published in early August - 114,000 compared with 175,000 expected - and the downward revisions of the previous two months resonated as much as they have, this is largely because of the Sahm rule, theorised by the American economist Claudia Sahm (see 'The Long View' below). However, Claudia Sahm herself explained that this did not necessarily apply in the current economic conditions. The rise in the unemployment rate started from a low level and reflects an increase in the size of labour force rather than an increase in layoffs. In addition, the soft landing of the US economy appears to be continuing, as demonstrated by the month's publications, notably the ISM4 services index, retail sales and US consumer confidence.

The United States is not the only country to have had a turbulent start to the month. The Japanese central bank's surprise rate hike of 25 basis points on 31 July sent the yen soaring and the Nikkei plunging by around 20% in the days that followed. The rise in the yen has had repercussions for many investors, who borrow Japanese currency to finance highly leveraged investments in Western markets offering a better return (carry trade strategy). These sudden movements led to the unwinding of many positions in risky assets, on the Japanese stock market and on Western markets. Faced with these chain reactions, the BoJ5 sought to reassure the market, indicating that no further rate hikes were planned in the short term and that it would take volatility into account in its forthcoming decisions. The Nikkei ended August down just 1%.

The market rebound over the month was also driven by other positive signals. On the one hand, US corporate earnings continued to demonstrate solidity - even though some of the Magnificent 7 published mixed results, in a market with low liquidity.

On the other hand, disinflation continued in the US and the Jackson Hole speech later in the month confirmed that the Federal Reserve did indeed intend to cut rates at its next meeting and had all the leeway it needed to react should the job market show signs of weakness.

In the wake of concerns about employment, the market fully integrated the hypothesis of a Fed rate cut of 50 basis points as early as September, with a probability of 100%, before converging instead on a 25bp cut without discarding the initial scenario. This led short rates to fall sharply at the start of the month and had a favourable impact on bonds. The performance of US Treasuries showed a gain of around 1.3%1over the month, while European sovereign bonds rose by 0.4%. This fall in rates also benefited gold, which gained more than 2% in August. Lastly, emerging market assets, which are also sensitive to US interest rates, also gained almost 2%.

August therefore highlighted the risk of a downgrading of the economic outlook in the United States, but this is accompanied by the possibility of the Fed adopting a more accommodative policy than expected. Our central scenario does not include a recession in the US or Europe over the next 12 months.

Goldilocks scenario still leads the race

Graph of the month

Macro review and outlook

Macroeconomics: Central banks on the road to lower rates

In recent months, there have been worrying signs of a downturn in the United States and Europe, but the global economy is still showing a degree of resilience. Activity in the services sector is offsetting the weakness in manufacturing output. Job creation is slowing but remains positive. Household consumption remains healthy overall, fuelling annualised global GDP6 growth of around 3%7. Certainly, there are some signs of weakness, but central banks on both sides of the Atlantic now seem ready to introduce a more flexible policy, the effects of which should partly offset the expected tightening of fiscal policies in 2025 and will be felt well beyond national economies.

United States: an active start to the new year for the Fed

The second estimate of US real GDP growth in the second quarter was 3%7, confirming that the economy was operating above its potential. It was driven in particular by resilient consumer behaviour, with the consumption component of GDP rising sharply and the consumer confidence index remaining solid. Retail sales continued to surprise on the upside this summer.

It is true that the increase in consumption appears to be due primarily to a fall in the savings rate rather than an increase in income, and that savings reserves now appear to have been exhausted. However, this is not a cause for concern at this stage. Instead, we expect consumption to slow slightly over the coming months. Disposable incomes should remain buoyed by a still-resilient labour market and continued disinflation. So Americans should be able to take advantage of relaxed financial conditions, with falling interest rates and a good performance from equities. This should support consumption.

The opposite scenario would of course be a sharp deterioration in the labour market. Generally speaking, however, redundancies remain moderate and mainly concern temporary rather than permanent jobs. The level of corporate margins does not argue in favour of a marked adjustment in employment and the level of corporate debt remains reasonable, thus avoiding any forced deleveraging. The upward trend in the unemployment rate (from a very low level) is more a reflection of a situation in which job creation is slowing and lagging behind growth in the active population. According to the leading indicators, a wave of mass redundancies is not on the cards.

A wait-and-see attitude therefore prevails in the run-up to the presidential election. But most companies see no sign of recession in the short term. Projects may be postponed but rarely cancelled.

Manufacturing activity indicators fell over the summer. The slowdown is concentrated in industry and real estate. But the combination of new orders and inventories components does not suggest that industrial production will be very negative in the months ahead. And activity is picking up slightly in services, which again helps to compensate. Activity is slowing in the United States, but from a level that was relatively high. Macroeconomic surprise indicators are stabilising, and the Atlanta Fed's nowcast GDP indicator suggests GDP growth of around -2%7 in Q3, which is still respectable.

Moreover, one of the major developments in the US economy in recent months has been the persistence of disinflation. Goods and food prices are now stable or falling, rent inflation should ease over time and wage inflation is decelerating as the labour market rebalances. Wage growth (around 3.5%7 over the year) and unit labour costs (close to 2%7) are now becoming compatible with the Fed's stated inflation target. Similarly, the PCE8 core price index, the inflation measure favoured by central bankers, has risen by just 1.7% on an annualised basis over the past three months. All the conditions are in place for rate cuts and the rapid normalisation of monetary policy. The last FOMC meeting9 confirmed that the majority of members were in favour of this option.

The market is expecting rates to fall by 100 basis points10 between now and the end of the year, with two cuts of 25 basis points and one of 5010. In 2025, rate cuts could once again total 100bp, with a 25bp cut at each meeting, notwithstanding a scenario in which the Fed would take a break in early 2025 because it would be faced with inflationary measures such as higher tariffs or a radical change in immigration policy (see Trump programme). This latter scenario is clearly not being taken on board by the market.

In the end, our central scenario for the United States remains one of continued soft landing, against a backdrop of monetary normalisation, with growth likely to be in the region of 1.5%-2% annualised over the next few quarters.

Eurozone: potential still delayed

In the eurozone, activity slowed sharply over the summer.Consumption remains very mediocre. The gloom persists, with low consumer confidence affected by an uncertain environment and industry back in recession. This is reflected in Composite PMI indices10 close to 50, corresponding to an economy in virtual stagnation. Nevertheless, we believe that the potential for growth and consumption in Europe has only been delayed; it has not disappeared. Households have extremely high levels of savings, coupled with rising wages: + 4% to 5%10. With inflation back down to around 2%, Europeans are enjoying a significant gain in real purchasing power. They should be able to take advantage of this once the context is less uncertain, particularly in France and Germany.

Germany remains in the grip of a manufacturing recession, exacerbated by the government's inability to push through reforms. Consumer and private sector confidence is low, which does not encourage spending or investment.

In France, the Olympic Games led to a rebound in growth in the third quarter, as shown by the latest PMI services index. However, the uncertainties surrounding the forthcoming budget vote are still a burden. The prospect of a political deadlock looms large at a time when France is being called on by Brussels to reduce its deficit. The rebound in growth is therefore likely to be only temporary, and the risks for the next 6 to 12 months are high.

Southern Europe, which has held its own so far, is also experiencing a slowdown. The services PMI is still buoyant, but down on previous months.

All in all, what is desperately needed in the eurozone are growth drivers. Household consumption (0.8% in 2024 after 0.6% in 202310) remains weak, and the savings rate too high, while employment is slowing. Extra-European exports are suffering from rising trade tensions and a lack of overall competitiveness in European industry. Finally, fiscal policies are becoming more restrictive. However, there has been some good news, notably a slight upturn in lending to businesses and individuals in recent months.

This situation lends credence to the idea of a further rate cut by the ECB12 as early as October, following the cut in September, although this does not appear to have been confirmed at the latest meeting. As expected, disinflation is taking longer in the eurozone than in the United States, due to continued robust growth in wages, particularly in Germany, and prices in services. The ECB seems to want to take time to reflect, even if it means postponing the next cut until December. Another key variable is the pace of Fed rate cuts, which should determine monetary policy in the eurozone.

China: more disappointment

Chinese economic activity contracted further in the second quarter, suffering from a fall in private domestic demand. The Chinese are experiencing a negative wealth effect, weighed down by the fall in property and equities. They prefer to keep substantial precautionary savings, especially as the costs of healthcare and funding their retirement are their responsibility.

The coming months could become even more complex for China, whose trade relations with many of its partners are becoming increasingly strained: Turkey, Canada, the European Union, the United States... Business is off to a very sluggish start for the new quarter.

While it is true that the Chinese Central Bank is supporting credit, this remains relatively ineffective in the absence of consumer spending and corporate investment in major projects. The prospect of 5%13 growth over the year is therefore not assured, and the country could feel the full impact of any increase in US tariffs in the wake of the presidential election. Inflation is expected to remain stable at between 1% and 2%10.

Although clouds are gathering over China, the economy is not experiencing a sharp downturn that would call into question our global soft landing scenario.

A look at the US election

Kamala Harris's candidacy has reignited the US election campaign, and a Republican or Democrat victory will not necessarily have the same impact on the outlook for growth, inflation and monetary policy in the United States.

Corporate tax rate proposals are a key point of differentiation for financial markets. Kamala Harris is proposing an increase in corporation tax to 28%10 from the current rate of 21%10, while Donald Trump is proposing a reduction to 15%10.

Similarly, a large number of temporary tax reductions enacted in 2017 are due to expire at the end of 2025. Donald Trump aims to broadly extend current tax rates, while Kamala Harris could be more selective, favouring the least well-off households. A divided government would, on the face of it, make an agreement difficult to reach, which would limit the extension of tax cuts.

Generally speaking, Donald Trump's policy is seen as more inflationary and therefore more bullish on interest rates and the dollar than that of his opponent,. For bondholders, a Trump victory would therefore be more unfavourable than a Kamala Harris victory.

Nevertheless, in the event of a victory for the Democrats, particularly in both Houses, we should not underestimate the extent of budgetary support for the most disadvantaged or for young people through tax credits, as well as support for growth and consumption. According to initial estimates, this could boost US growth by between half a percentage point and one percentage point as early as 2025, something that the market has not yet fully integrated.

In short, a Donald Trump victory with a divided Congress could lead to higher tariffs and fewer migratory flows, without any significant tax cuts, creating a risk of mild stagflation.

A D.Trump victory in both houses could lead to more tax cuts, more tariffs and less migration and would be clearly reflationary.

A Kamala Harris victory with a divided Congress would not, on the face of it, bring about any major changes to the current situation

A K.Harris victory in both houses would mean higher taxes on corporations and high earners, a tax on share buybacks and more fiscal stimulus for the most disadvantaged. Energy policies would also be very different, with a Harris victory leading to more 'green' investment.

The Long View

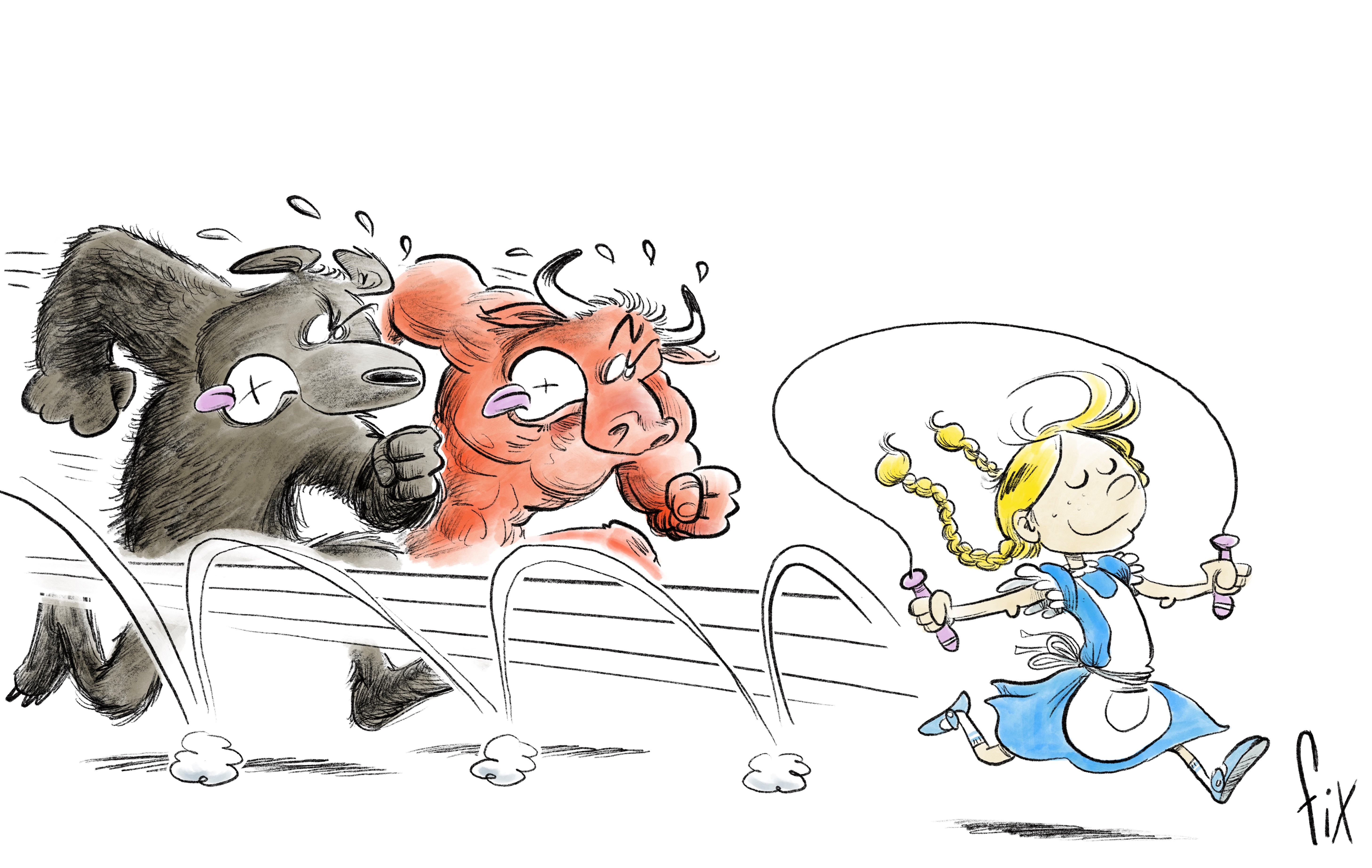

Market panic: the summer of sheep

And suddenly, the Nikkei..

On 5 August, the Nikkei index collapsed by 12.4%14, its worst daily performance since the October 1987 crash, following an initial fall of almost 6%14 on two August. This was followed by sharp falls in other indices: a mini panic took hold of the markets, yet another... Consensus quickly emerged as to its causes: they were to be found in the unwinding of carry trade positions in the yen triggered by the surprise rate hike by the BoJ (Bank of Japan) and, above all, in US employment data which rekindled fears of a possible recession in the US, at least in the light of the now famous Sahm's rule. A few warnings in a wave of second-quarter results that were less enthusiastic overall than those seen since 2021 then added a little doubt to the trends. And some commentators, already critical of a rise in rates that they had not anticipated, jumped into the breach to claim that these employment figures showed that Jerome Powell had quite simply made a mistake in monetary policy by leaving rates at such levels for so long. However, none of these important factors would appear to justify a reduction of this magnitude. And the market was able to correct it.

Carry Trades

The low interest rate policy pursued by the BoJ for the last thirty years had of course created significant opportunities for carry trades, which are leveraged strategies that involve borrowing in a low-rate currency and reinvesting the proceeds in higher-yielding assets in another currency.

For years, all you had to do was borrow yen and buy assets in dollars, euros or virtually any other currency to benefit from attractive yield spreads with fairly manageable risks. The last of the major central banks to normalise its policy, the BoJ last month put an end to no less than eight years of negative key rates. In so doing, it threatened the fine edifice of carry trade positions by reducing their attractiveness on the one hand, and by triggering margin calls on the part of creditors in the face of the generation of loss on the other. This, of course, forced some players who played these strategies to sell shares, or even close positions, to raise funds and settle these margin calls, leading to further losses that led to other margin calls. The logic was sound, except that no market player was really able to provide the scale of these carry trade positions: no one seemed in a position to evaluate them accurately, even if some analysts did have the merit of attempting to do so very cautiously.

Admittedly, a market panic caused by an unquantified phenomenon can be justified, provided that the said phenomenon has the potential to contaminate many players in the financial system. However, in the case of yen carry trades, there was nothing to indicate that they involved much more than specialists and systemic investors with the means to hedge their positions. Coupled with the BoJ's obvious attention to the consequences of its actions, there was probably not enough to fuel a crash for long on this factor, even if it should not be taken lightly.

Sahm vs Sahm

The Sahm rule states that if the moving average of the US unemployment rate is more than half a percentage point above its lowest level in the previous twelve months, then a recession has probably begun. As it happens, the publication of July's employment figures indicated that this was now the case, sending the markets into a panic.

However, Claudia Sahm, who established the rule that bears her name, was quick to explain that it should not be interpreted literally in the current context, which is characterised by seasonal factors. To sum up, she reminded us that her rule, in order to become active, presupposed more or less constant levels of labour supply; however, this is not the situation in North America, where the labour market remains dynamic albeit. No longer able to absorb all jobseekers, not because the economy is weakening, but mainly because the number of jobseekers has swollen as a result of the Biden administration's logic use of immigration to absorb the labour shortage in the months following the Covid restrictions and thus help curb inflationary trends. To put it plainly, the unemployment rate is rising not because a recession is looming, but because strong job creation is no longer sufficient to cater for all jobseekers, whose numbers have expanded to unusual proportions under constraints that were necessary at the time, but which are now dissipating.

There is indeed an underlying issue concerning employment in the United States, as a result of the elimination of imbalances created by the post-covid crisis and productivity gains that are being generated. For the time being, however, the data do not indicate the conditions for a recession. Even Claudia Sahm says so... On the other hand, they clearly point to an inevitable slowdown, which previous statistics have already shown to be taking place.

Anecdotal panic or a flaw in the markets' armour?

So the two main arguments put forward to explain the panic at the beginning of August, although rational, both lacked the substance and force that could have justified its scale; and yet it happened, and in what proportion! So what can we learn from it? That, once again, markets can become dysfunctional, and that the relentless development of ETFs and algorithmic trading and management is not to blame. The latter, by construction, amplify market movements to the point of aberration; in this case, falling valuations and rising volatility form automatic sell signals which, of course, exacerbate this fall, which forces another fall and so on. As for ETFs, again by design, they do nothing more than adjust to the markets, mechanically, selling what is already depreciating and buying what is appreciating, relatively speaking.

The development of these two tools, each of which is useful in its own way, becomes problematic when it reduces fundamental management to the bare essentials. The share of the latter in the flows handled is becoming too small to play an effective role in price formation. We are now seeing bond traders on the Old Continent waiting for Nvidia's results and the reaction of the equity markets before quoting European high yield bonds, even though the relationship between a company rated AA-/ Aa3 and which has not issued any debt in euros and European high yield remains quite tenuous. It seems inevitable that regulators will take up this issue. There can be no doubt that if the signals sent out in early August had been better substantiated and more serious, the combined herd effect of quantitative management and ETFs could have added a financial crisis to the weak signs of economic anxiety, thereby precipitating an economic crisis that had originally been nothing more than a simple slowdown. And without further delay, let's hope that the world's largest sovereign wealth fund, which prides itself on its responsible, long-term policy, will also take up this issue.

For the moment, reactive forces are still playing their part in preventing self-fulfilling mechanisms from kicking in. Let's not wait until they can no longer do so before correcting the replication bias, and hence exaggeration, that the markets have now placed at the heart of their operations. That would be too late. So, while we wait for an accident that would be one too many, this also creates great opportunities for active managers who know how to keep their cool in these phases. When passive management helps active management..